Ethical Issues in Health

Introduction

Ethics

Ethics is a branch of philosophy

Ethics is ‘the formal study of the principles on which moral rules and values are based’

Morals refer to those beliefs about how people ‘ought’ to behave. These debates are about right and wrong, good and bad, and duty

Morals are products of culture, linked to historical contexts.

Morals vs Ethics

“The moral question is, what should I do?, and the reply consists of proposing an action (or an omission).”

“Ethics asks, why should I do it?: it positions itself at a secondary, contemplative level and the reply consists of an argument”

Why do we need ethics in research?

The physician Hippocrates (5th century, B.C.E.) Oath of Hippocrates.

“medical care should be practiced in such a way as to diminish the severity of the suffering that illness and disease bring in their wake, and the physician should be acutely aware of the limitations concerning the practical art of medicine and refrain from any attempt to go beyond such limitations accordingly” -> Taylor (2019)

HCPC Code of Conduct

The Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC) is a regulator set up to protect the public. It regulates 16 professions including prosthetists / orthotists.

| The Code |

|---|

| Promote and protect the interests of service users and carers |

| Communicate appropriately and effectively; |

| Work within the limits of their knowledge and skills |

| Delegate appropriately |

| Respect confidentiality |

| Manage risk |

| Report concerns about safety |

| Be open when things go wrong |

| Be honest and trustworthy |

| Keep records of their work |

Difference between health care ethics and research ethics

“Once patients agree to be treated, they trust that the physician will act in their interest, or at least will do no harm”

“In research, which is outside the beneficent context of the physician–patient relationship, this trust may be misplaced, because the physician’s primary goal is not to treat; rather, it is to test a scientific hypothesis by following a protocol, regardless of the patient-subject’s best interest” -> Shuster (1997)

Ethics of Health Promotion

“The ethics of health promotion involves the careful examination of the authority or legitimacy of health promoters. It asks us to explain and justify our choice [of intervention]” (Bunton & McDonald 2002, p.274)

Raphael (2002) argues that “ethical health promotion requires explicit recognition of the interactions among ideologies, values, principles and rules of evidence” (p.355)

Theories and Practices

Brief History of Research Ethics

1906 – Cholera Vaccine Trial

- Lack of informed consent

1947 – Nuremberg Code

1964 – Declaration of Helsinki

1972 Tuskegee Syphilis Study

1996 Good Clinical Practice

2005 Research Governance Framework 2nd edition

The Function of Ethical Theory

There is no correct ‘ethical formula’ for decision making and no single set of ‘right answers’ (Bunton & McDonald, 2002).

It is not designed to provide answers…but to inform judgements to help people work out what course of action should be taken

Most ethical theories fall into two types:

- Deontological

- Consequential

Deontology

Deontology – comes from the Greek work deontos, meaning duty.

Deontologists hold that we have a duty to act in accordance with certain universal moral rules.

Duty

- Deontologists hold that there are universal moral rules that it is our duty to follow.

- Many of the philosophical discussions about the nature duty are based on Immanuel Kant’s ‘Categorical Imperative’ (Kant 1909 cited in Naidoo & Wills 1994)

Kant’s Theory

Act as if your action in each circumstance is to become law for everyone, yourself included, in the future.

Always treat human beings as ‘ends in themselves’ and never as merely ‘means’. A moral rule is one that respects all people.

Duties incorporated in ‘codes of practice’

- Practitioners have a:

- Duty to care

- Duty to be fair

- Duty to respect personal and group rights

- Duty to avoid harm

- Duty to respect confidentiality

- Duty to report (SHEPS 1997)

Consequential/Utilitarianism

Consequential ethics are based on the premise that whether an action is right or wrong will depend on its end result.

Consequentialism differs from deontology because it is concerned with the ends and not only the means.

Utilitarianism is the most well known branch of consequentialism.

The Utilitarianism principle is that a person should always act in such a way that will produce more good or benefits than disadvantages.

- E.G. John Stuart Mill & Jeremy Bentham aimed for ‘the greatest good or pleasure for the greatest number of people’.

Limitations of Consequentialism

If the aims of all actions is to achieve the greatest good, does this justify harm or injustice to a few if society benefits?

Should the interests of the majority always take precedence over those of the individual?

Simplification of Approaches

- ‘Rule-based’

- As a rule is it wrong to interfere in someone’s life? Should we respect their privacy/personal liberty?

- ‘Consequence-based’

- Will it produce good consequences?

- What are ‘good consequences’? How can we know what they will be?

The Four Principles of Biomedical Ethics

| Principle | Description |

|---|---|

| Respect for Persons/Autonomy | Acknowledge a person’s right to make choices to hold views, and to take actions based on personal values and beliefs |

| Justice | Treat others equitably, distribute benefits/burdens fairly |

| Nonmaleficence (do no harm) | Obligation not to inflict harm intentionally. In medical ethics, the physician’s guiding maxis is “First, do no harm” |

| Beneficence (do good) | Provide benefits to persons and contribute to their welfare. Refers to an action done for the benefit of others. |

“Every biomedical research project involving human subjects should be preceded by a careful assessment of predictable risks in comparison with foreseeable benefits to the subject or to others. Concern for the interests of the subject must always prevail over the interests of science or society” -> (Declaration of Helsinki 1975, cited in Singleton & McLaren 1995, p.118).

Autonomy

Autonomy derives from the Greek word autonomous meaning self-rule.

Autonomy is only constrained by:

- Reason and the ability to make rational choices

- The ability to understand one’s environment

- The ability to react to one’s environment

In addition, a person needs to be free from pressures such as fear and want and have the personal and social circumstances to make any chosen action possible.

Autonomy must, therefore, be thought of not as an absolute but as an attainable, to a greater or lesser extent.

Not everyone has autonomy. When a person’s capacity for rationality is affected in some way, decisions are often taken on their behalf on the basis that ‘they do not know what’s best for them’.

It was not until the 20th Century that women were deemed able to make a rational choice in a democratic vote.

It was only in 1989 that the Children’s Act first recognized the rights and capacity of children to have a say in their care.

Creating/respecting Autonomy

Seedhouse (1988) makes a distinction between creating autonomy and respecting autonomy in working for health.

Creating autonomy – is making an effort to improve the quality of a person’s ability to choose freely by trying to enhance what the person is able to do…often called empowerment

Respecting autonomy – is agreeing to the wishes of the individual, whether or not you approve of their wishes.

Justice

Seedhouse (1988) states that ‘This is a question which is at least as difficult to provide an answer to as the question ‘What is health’? (p.108)

Philosophers suggest three versions of justice:

- The fair distribution of scarce resources

- Respect for individual and group rights

- Following morally acceptable laws

- The formal principle of Justice is that ‘equals ought to be treated equally’

Beneficence and non-maleficence

- The principle of beneficence makes the point that ‘we should try to practice to do good and not evil, not merely that we should wish to do so’ (Seedhouse 1988 p.136)

- Frankena (1963) (cited in Seedhouse 1988), summed up the principle of beneficence as:

- One ought not to inflict evil or harm (what is bad)

- One ought to prevent evil or harm

- One ought to remove evil

- One ought to do or promote good

Applying the Principle

Need to be clear about:

- What counts as good?

- What counts as evil

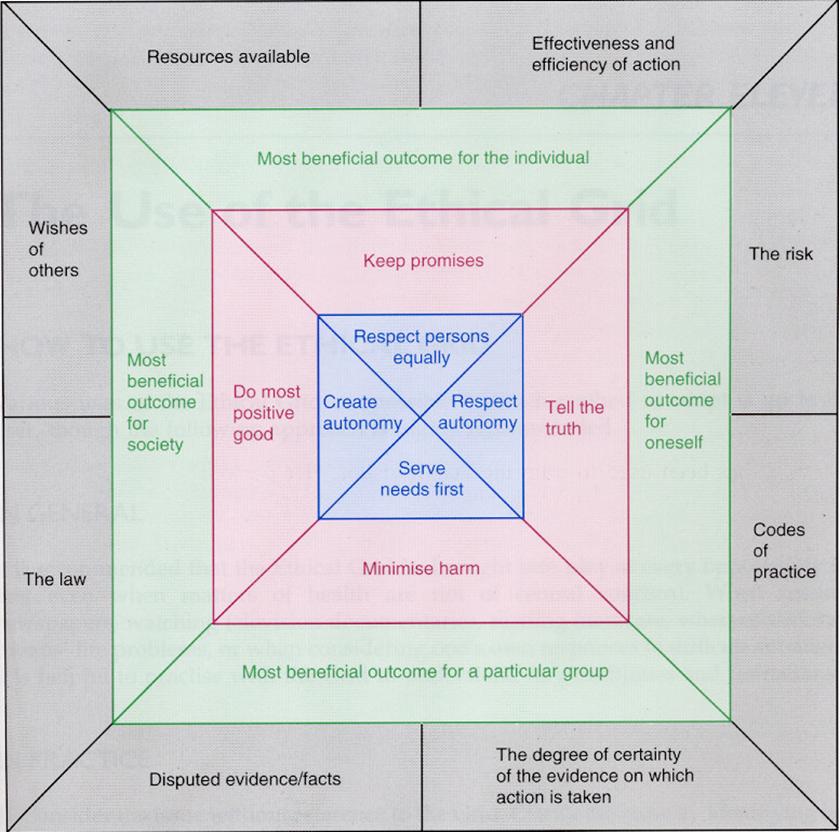

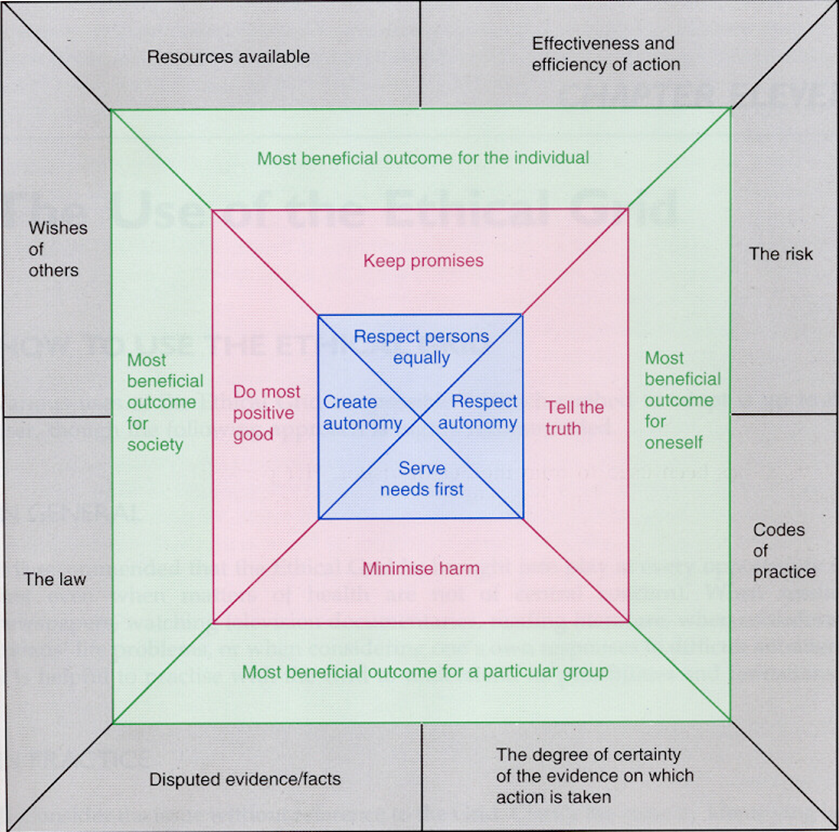

Seedhouse - Ethical Grid

Developed to aid clinical decision making, with the layers helping support moral reasoning.

It can help remind the clinician of the range of considerations which might affect his deliberation.

The Ethical Grid

Designed to provide a structured way of thinking about something

Based on Moral Theory

It will rarely be necessary to consider a problem using every box, it is important to consider each situation in the light of each layer to engage in ‘moral reasoning’.

Nolan Principles

- This includes people who are elected or appointed to public office, nationally and locally, and all people appointed to work in:

- the civil service

- local government

- the police

- the courts and probation services

- non-departmental public bodies

- health, education, social and care services

- The principles also apply to all those in other sectors that deliver public services. They were first set out by Lord Nolan in 1995 and they are included in the Ministerial code.

- Selflessness

- Integrity

- Objectivity

- Accountability

- Openness

- Honesty

- Leadership

Public Health Ethics

Lee & Zarowsky (2015) suggest three element for public health practitioners relating to ethics:

the notions of “common” and “professional” morality,

an understanding of the practice and content of modern public health and especially its practical, solution-focused orientation,

an appreciation of the history of public health as integrally linked to evolving and contested views of the relationship between citizens, science and the state

Summary

Ethics often relies on a set of judgements based on moral areas, so there is often no single or universal way forward.

Ethical guidance and codes in health are less set than some areas but the principles of ethics translate across all areas.

References

Bunton R. & McDonald G. (2002) Health Promotion: disciplines, diversity and developments, 2nd edn, Routledge

Naidoo & Wills (2000) Health Promotion (chapter 6)

Nuffield Council On Bio-Ethics (2007) Public Health Ethical Issues http://www.nuffieldbioethics.org

Ethical issues in global health http://www.who.int/ethics/topics/en/

Global Health Ethics: key issues http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/164576/9789240694033_eng.pdf;jsessionid=C18FD48A42FFC4CB147E0C3DC3C6CE2D?sequence=1

Arksey, H & Knight, P (1999) Interviewing for Social Scientists: An introductory Resource with examples

Ramcharan, P & Cutcliffe, JR (2001) Judging the ethics of qualitative research: considering the “ethics as process” model

Singleton, J & McLaren, S (1995) Ethical foundation of health care: responsibilities in decision making

Royo-Bordonada MÁ, Román-Maestre B. Towards public health ethics. Public Health Rev. 2015;36:3. doi:10.1186/s40985-015-0005-0

Hart, T (1971) The Inverse Care Law Ruschmann (1980) Mandatory Motorcycle Helmet Laws in the Courts and in the Legislatures

Shuster (1997) Fifty Years Later: The Significance of the Nuremberg Code. N Engl J Med 1997; 337:1436-1440 https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJM199711133372006

Seedhouse (1988) Ethics: The heart of health care

Taylor (2019) Health Care Ethics. The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy (IEP) (ISSN 2161-0002) https://www.iep.utm.edu/h-c-ethi/