Heart Pathophysiology

Introduction

Expand

It is critically important to consider how cardioprotection is achieved in heart diseases because mortality and morbidity of heart diseases have increased all over the world, and the burden from the viewpoint of not only the individual patient but also social and economical aspects is increased as we begin the 21st century.

To decrease this burden, it is essential to protect the heart against ischemic stress, and there are three different aspects to achieve cardioprotection in ischemic hearts.

1) Acquisition of Cardioprotection before the occurrence of Ischemia

First, acquiring tolerance against ischemia and reperfusion injury before the onset of ischemia is effective for patients with coronary artery disease or coronary risk factors.

For example, development of collateral circulation in advance can reduce the severity of ischemia when coronary occlusion occurs.

Preventing rupture of the atheroma is another paradigm used to attenuate the incidence of acute coronary syndrome.

Furthermore, if the trigger mechanisms of cardioprotection due to ischemic preconditioning are elucidated, they can be applied in high-risk patients before acute myocardial infarction.

2) Develop the tool for the treatment of ischemic and reperfusion injury

Second, it is also important to develop the tool for the treatment of ischemic and reperfusion injury.

To our knowledge, we still do not have the drugs or tools to decrease either infarct size or cardiac remodeling in patients with acute myocardial infarction, except for recanalization therapy.

Even when patients survive acute myocardial infarction, chronic ischemic heart failure may occur

3) Obtain drugs to treat chronic ischemic heart failure.

Therefore, as the third paradigm, we need to obtain drugs to treat chronic ischemic heart failure.

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and beta-blockers have been proven to attenuate the mortality and morbidity of chronic heart failure; how ever, we do not believe that these drugs are powerful enough to treat chronic heart failure with full satisfaction.

1) Acquisition of Cardioprotection before the occurrence of Ischemia

Expand

When the effective pretreatment to attenuate the ischemic injury is applied prior to the occurrence of ischemic heart disease in subjects with high-risk factors for acute myocardial infarction, such as hyperlipidemia, smoking, and hypertension, the pretreatment before the onset of myocardial ischemia will become an effective method for the attenuation of ischemia and reperfusion injury.

Ischemia is a condition in which the blood flow (and thus oxygen) is restricted or reduced in a part of the body. Cardiac ischemia is the name for decreased blood flow and oxygen to the heart muscle.

Ischemic heart disease is the term given to heart problems caused by narrowed heart arteries. When arteries are narrowed, less blood and oxygen reaches the heart muscle. This is also called coronary artery disease and coronary heart disease.

This is similar to the immunization therapy for infectious diseases such as mumps.

A: Plaque Rupture

Expand

Since it is well recognized that acute myocardial infarction occurs due to the abrupt plaque rupture followed by the accumulated platelet aggregation, it is critically important to prevent plaque rupture in patients with coronary artery disease.

One possibility is to apply cholesterol-lowering therapy.

Although pravastatin, one of the inhibitors of HMG-CoA reductase, is reported to decrease stenotic coronary artery only to a modest extent, it decreases the incidence of cardiac death in patients with coronary artery disease or in high-risk patients (1).

It is suggested that pravastatin stabilizes the plaques and prevents the rupture of plaques.

Pravastatin or simvastatin may decrease the content of cholesterol and the accumulation of macrophages at the stenotic site of the coronary artery and reduce oxidative stress and inflammatory actions.

Casscells et al. (2) reported that active plaques produce heat, suggesting that inflammatory reactions are involved in active plaques, which may make the fibrous cap fragile.

This inflammation may be caused by bacteria such as chlamydia or by lipid metabolites which activate monocytes.

Because probucol, an antioxidant drug with a moderate cholesterol-lowering capability, is very effective in decreasing the mortality and morbidity in patients with coronary artery disease, oxidative stress may be an important factor for the onset of plaque rupture.

Therefore, oxidative stress at the atheroma attacks fibrous caps, although there is no direct evidence or report of the methods to prevent plaque rupture at present.

B. Collateral Circulation

Expand

Development of a collateral circulation from nonischemic myocardium to ischemic myocardium is an important strategy in attenuating the severity of myocardial ischemia when coronary arterial occlusion occurs.

The fibroblast growth factor (FGF), transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) families are known to be important growth factors for angiogenesis (3–5).

Basic FGF has been proved to be responsible for the development of collateral circulation (6).

Yanagisawa et al.(6) showed clearly that basic FGF levels increase after the onset of myocardial infarction, suggesting that basic FGF may play a role in angiogenesis of collateral circulation in patients with coronary artery disease.

However, heparin is also known to cause angiogenesis because heparin activates HB-EGF, which induces the migration and proliferation of smooth muscle cells (7, 8).

Furthermore, VEGF is also known to cause potent angiogenesis due to the proliferation and migration of endothelial cells (9).

Interestingly, adenosine is shown to increase mRNA and the protein levels of VEGF (10), suggesting an important role for the development of collateral circulation.

Furthermore, adenosine increases the proliferation and migration of endothelial cellsin vitro (11).

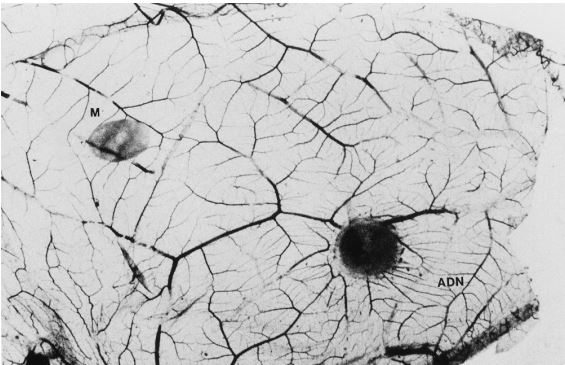

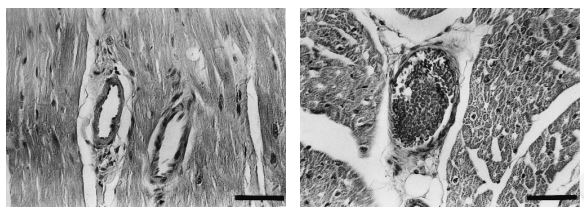

However, in the in vivo condition, adenosine stimulates angiogenesis on the chick chorioallantoic membrane (Fig. 1) (12), and dipyridamole increases adenosine-induced angiogenesis.

Finally, repeated administration of dipyridamole in vivo for several weeks increases the regional myocardial flow of the ischemic area compared with the control, and this effect cannot be mimicked by diltiazem (13).

This result suggests that coronary vasodilation per se does not affect the development of collateral circulation, but the enhancement of adenosine during the administration of dipyridamole can increase the development of collateral vessels.

Taken together, either or all of the growth factors, such as VEGF, HB-EGF, and basic FGF, may induce angiogenesis in patients with coronary artery disease, which may constitute cardioprotection against ischemia and reperfusion injury.

Furthermore, pharmacological interventions, such as heparin or adenosine administration, may enhance angiogenesis via the induction of growth factors.

Gene transfection may lead to the development of collateral circulation (5, 14).

Indeed, Losordo et al. (5) initiated a phase 1 clinical study to determine the safety and bioactivity of direct myocardial gene transfer of VEGF as the sole therapy for patients with symptomatic myocardial ischemia.

In five patients who had failed conventional therapy for angina, naked plasmid DNA encoding VEGF (phVEGF165) was injected directly into the ischemic myocardium.

They found that all of the patients had a significant reduction in angina and that the postoperative left ventricular ejection fraction was either unchanged or improved.

Objective evidence of reduced ischemia was documented using dobutamine single-photon emission-computed tomography (SPECT) imaging in all patients.

Coronary angiography showed an improved Rentrop score in all of the five patients.

Therefore, gene transfection to increase collateral circulation may become one of the potential treatments of coronary artery disease.

Another method used to increase ischemic tolerance is to induce cardioprotection prior to the ischemia of acute myocardial infarction, and one potential way is to induce in advance the infarct size-limiting effect of ischemic preconditioning in patients with coronary artery disease.

C. Ischemic Preconditioning

Expand

Ischemic preconditioning has received much attention from both basic researchers and clinicians. This was first described by the research group of Murry et al. (15).

Results to date have shown that ischemic preconditioning limits infarct size to 10–20% of the risk area in the reperfused ischemic myocardium (16–19).

Liu et al. (16) have implicated endogenous adenosine as a trigger or mediator in ischemic preconditioning by demonstrating that the administration of 8-(sulphophenyl)theophylline abolishes the salutary effect of ischemic preconditioning.

These investigators have hypothesized that ischemic preconditioning occurs via adenosine A1 receptor activation.

Adenosine A1 receptor activation activates protein kinase C (PKC) via the activation of phospholipase C, and several investigators, including the authors, found that the activation of PKC is transiently observed after the procedure of ischemic preconditioning (18, 19).

Furthermore, the inhibition of PKC blunts the infarct size-limiting effect of ischemic preconditioning (17–20).

Therefore, at present, activation of protein kinase C is believed to be a common pathway in triggering cardioprotection.

The next question is how protein kinase C activation triggers the infarct size-limiting effect of ischemic preconditioning.

Activation of protein kinase C opens KATP channels, and the opening of KATP channels may be cardioprotective against ischemia and reperfusion injury.

The opening of mitochondrial KATP channels is also activated via protein kinase C (20, 21), suggesting that it is mitochondrial KATP channels which are responsible for cardioprotection.

It was shown that the activation of PKC increases ecto-5β-nucleotidase activity (Fig. 2) and mediates the cardioprotection via the enhancement of adenosine production in ischemic preconditioning (17, 18).

Cardioprotection due to the ischemic preconditioning procedure disappears in several hours, and this disappearance could be attributable to dephosphorylation of the cardioprotective proteins or enzymes.

Interestingly, cardioprotection will reappear in 24–48 hr after the ischemic preconditioning.

This is known as the second window of ischemic preconditioning (22, 23).

Marbe et al. (22) reported that HSP72 induction is important in mediating the infarct size-limiting effect of ischemic preconditioning, and Kuzuya et al. (23) reported that Mn-superoxide dismutase (Mn-SOD) induction may contribute to the cardioprotection in ischemic preconditioning.

2) Acquisition of Cardioprotection during Ischemia and Reperfusion

Expand

There are two different ways to find the method to directly decrease ischemia and reperfusion injury. One is to find mediators of the infarct size-limiting effect of ischemic preconditioning, and the other is to invent drugs that attenuate the ischemia and reperfusion injury independent of cardioprotection mechanisms of ische- mic preconditioning. Because the former was discussed briefly above as well as in Chapter 50, the latter strategy is mainly discussed here.

A. Factors That Cause Ischemia and Reperfusion Injury

Expand

There are many factors that constitute ischemia and reperfusion injury, and these factors seem to synergistically cause cellular injury in the heart.

1. ATP Depletion

Intracellular ATP levels are thought to determine the turning point between reversible and irreversible cellular injury.

This is because the maintenance of intracellular homeostasis is energy dependent: Ca2 pump, Ca2 ATPase, and interaction of actin and myosin.

A 90% decrease in ATP coincidentally results in the irreversible deterioration of the myocardium (24), leading to the idea that depletion of ATP content in reperfused myocardium may be a critical factor in the process of irreversible injury.

However, when adenosine is administered throughout ischemic and reperfusion periods, a 90-fold increase of ATP synthesis is obtained in the reperfused myocardium (25).

It is known that (1) adenosine stimulates glycolysis in rat hearts, (2) intracoronary infusion of adenosine increases glucose uptake, and (3) dipyridamole enhances glucose uptake accompanied by an increase in myocardial ATP in the newborn lamb.

Thus, enhanced glucose metabolism by adenosine may contribute in part to a decrease in the rate of ATP depletion during ischemia.

However, one may argue that the repletion of intracellular ATP via the administration of ribose or adenosine in the reperfused myocardium after the establishment of reperfusion injury does not promote recovery of contractile function, indicating that the recovery of intracellular ATP levels does not necessarily improve contractile function.

Adenosine-induced attenuation of contractile dysfunction may not be due to the recovery of ATP levels but rather to adenosine receptor activation.

Therefore, there is consensus that decreases in ATP levels are important for the determination of irreversible cellular injury, but may not be important in reversible cellular injury, such as myocardial stunning or hibernation.

2. Ca2+ Overload

Ca2 overload is thought to disrupt cellular membrane and intracellular homeostasis via the activation of calpain.

If this process occurs during ischemia and reperfusion injury, Ca2 overload may play an important role in ischemia and reperfusion injury.

When myocardial ischemia occurs, cellular acidosis increases which activates Na/H exchange via the accumulation of H with resulting increased intracellular Na levels (26).

Accumulation of Na causes Ca2 overload via Na/ Ca2 exchange.

It was shown that ischemia increases intracellular Ca2 levels in in vitro Langendorff hearts (27).

Furthermore, using the integrity of microtubules, Ca2-sensitive structures in the cells, as an index, we showed that Ca2 overload occurs in ischemic canine hearts (28).

Therefore, Ca2 overload is believed to occur in ischemic and reperfused hearts.

Because intracellular Na levels are increased before the rise in intracellular Ca2 levels and the inhibitor of Na/H exchange attenuates the Ca2 overload, the route of entry of Ca2 into the cells is thought to be via Na/H and Na/ Ca2 exchanges.

The question is how important Ca2 overload is for the pathophysiology of ischemia and reperfusion injury.

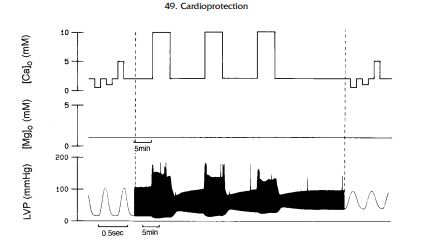

Transient Ca2 exposure in the ferret Langendorff preparation causes myocardial dysfunction (Fig. 3) (29), and attenuation of Ca2 overload attenuates the severity of myocardial dysfunction, suggesting that Ca2 overload may be an important cause of myocardial stunning.

However, there is no clear consensus that Ca2 overload contributes to the cause of myocardial necrosis.

Sustained intracellular acidosis, which inhibits Na/Ca2 exchange and thus Ca2 overload, is reported to attenuate myocardial ischemia (30), hinting that attenuation of Ca2 overload may limit myocardial necrosis (31), although intracellular acidosis is beneficial for the ischemia and reperfusion injury aside from the attenuation of Na/Ca2 exchange.

3. Free Radicals

When hearts are reperfused abruptly, oxygenderived free radicals and hydroxyradicals are produced and released from leukocytes and endothelial cells.

In the ischemic and reperfused condition, xanthine dehydrogenase changes to xanthine oxidase because xanthine oxidase is activated by protease sensitive to Ca2 accumulation.

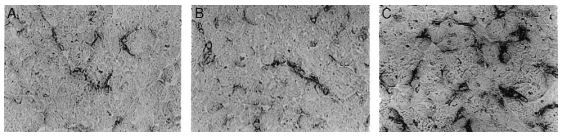

These radicals attack the cellular membrane and cause cellular damage via the inactivation of membrane enzymes, pumps, and proteins, such as Na/ K-ATPase, Ca2 channels, and ecto-5’-nucleotidase (Fig. 4) (32, 33).

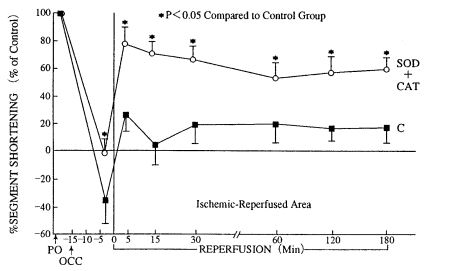

Gross et al. (34) reported that myocardial contractile dysfunction produced by 15 min oischemia and 3 hr of reperfusion is restored by superoxide dismutase (Fig. 5) (34).

Furthermore, Sekili et al. reported that hydroxyradicals are produced within a minute after the onset of reperfusion and that these radicals contribute to the generation of myocardial contractile dysfunction (35).

These results suggest that free radicals are important for the development of myocardial stunning; however, there is no clear consensus that free radials generated during ischemia and reperfusion may cause cellular necrosis.

Indeed, the clinical trial of the TIMI study revealed that 10 mg/kg of SOD does not attenuate infarct size in 120 patients with acute myocardial infarction (36).

This may be attributable to the fact that (1) oxygen-derived free radicals do not contribute to the formation of myocardial necrosis during ischemia and reperfusion or (2) the therapeutic time window of SOD may be narrow in patients with acute myocardial infarction.

However, oxidative stress causes vascular remodeling, such as thickening of intima and plaque rupture.

These effects may be very important in the genesis of acute myocardial infarction because drugs with antioxidant capability are reported to attenuate vascular events.

4. Catecholamines

When myocardial ischemia occurs, presynaptic vesicles release norepinephrine via the accumulation of Na.

Increases in Na levels activate the reverse uptake of norepinephrine (37), which facilitates norepinephrine release.

Norepinephrine activates both - and β-adrenoceptors: -adrenoceptor stimulation increases intracellular Ca2 levels and causes coronary vasoconstriction and β-adrenoceptor stimulation increases myocardial oxygen consumption.

These factors may cause deterioration of myocardial contractile and metabolic functions during ischemia and reperfusion.

Indeed, many experimental and clinical studies reveal that blockers of β- adrenoceptors are effective in the treatment of ischemic heart disease.

Interestingly, the amount of norepinephrine released during ischemia may enhance adenosine production and adenosine-induced coronary vasodilation through 1- and 2-adrenoceptor stimulations (38, 39).

Furthermore, -adrenoceptor stimulations are reported to increase myocardial endocardial blood flow at the expense of epicardial blood flow (40).

This may be attributable to differences in the sensitivity of endocardial and epicardial arteries during -adrenoceptor stimulation.

In this sense, norepinephrine release causes two opposite effects on vascular tone. High norepinephrine concentrations associated with severe prolonged ischemia may mask the adenosine-related cardioprotection and any favorable intramyocardial flow redistribution.

5. Microcirculatory Disturbances

Even if ischemic myocardium is reperfused by the once occluded coronary artery in acute myocardial infarction, coronary microvasculature does not necessarily receive enough flow.

Rather, myocardial perfusion becomes more heterogeneous; some areas receive enough flow, but some areas receive less flow than necessary.

This is called the ‘‘no reflow phenomenon’’ (41, 42).

The no reflow phenomenon is reported to predict the size of the myocardial necrosis and functional recovery in the chronic phase in patients with acute myocardial infarction (42).

The no reflow phenomenon can be caused by myocardial cellular injury, platelet plugging, leukocyte adhesion, and increases in the tone of small coronary vessels.

Kloner et al. (41) reported that 90 min of ischemia causes heterogeneous myocardial flow distribution, but that 40 min of ischemia does not.

Furthermore, the no reflow area is evident 10–12 sec after the onset of reperfusion, suggesting that the no reflow phenomenon is observed transiently at early phases of reperfusion.

Because 40 min of ischemia does not cause the no reflow phenomenon but causes myocardial necrosis, several investigators suggest that the no reflow phenomenon may not be involved in the pathophysiology of reperfusion injury.

However, because there are differences in the sensitivity to detect necrosis and the no reflow phenomenon and because there is clinical evidence to consider the no reflow phenomenon as a cause of myocardial injury, the no reflow phenomenon is believed to constitute reperfusion injury in ischemic heart disease.

6. Adhesion Molecule

Ischemia and reperfusion activate adhesion between leukocytes and endothelial cells.

Adhesion molecules in leukocytes are LFA-1, Mac-1, and the selectin family, and adhesion molecules in endothelial cells are ICAM1 and L-selectin (43).

There is contradictory evidence whether attenuation of these adhesion molecules using antibodies does or does not limit infarct size.

Therefore, we cannot determine the importance of the activation of adhesion molecules in the pathophysiology of ischemia and reperfusion injury.

7. Endothelin

Endothelin (ET) is divided into three subtypes: ET1, ET-2, and ET-3.

ET-1 causes potent vasoconstriction and it increases in patients with vasospastic angina and acute myocardial infarction.

There are two endothelin receptors, ETA and ETB , and ET-1 activates ETA .

Interestingly, when the ETA receptor antagonist is administered before or after the onset of myocardial ischemia, it decreases infarct size to 30–40% (44).

This indicates that endothelin plays an important role in the formation of reperfusion injury.

However, the mechanisms by which endothelin is deleterious to ischemic hearts, such as coronary vasoconstriction, Ca2 overload, or leukocyte or platelet activation, are not clear at present

8. Apoptosis

Ischemia and reperfusion cause apoptosis, and ischemic preconditioning attenuates the extent of cellular apoptosis during ischemia and reperfusion (45).

However, how much of the area of ischemic and reperfused myocardium becomes apoptotic or necrotic and the importance of apoptosis in the pathophysiology of diseased hearts have not yet been clarified.

B. Endogenous Factors That Cause Cardioprotection

Expand

1. Adenosine

Adenosine, produced not only in cardiomyocytes but also in endothelial cells, is known to be cardioprotective via adenosine receptors (38, 39):

- Attenuation of the release of catecholamine, β-adrenoceptor-mediated myocardial hypercontraction, and Ca2 overload via A1 receptors and

- increase in coronary blood flow and inhibition of platelet and leukocyte activation via A2 receptors.

Furthermore, adenosine inhibits renin release and TNF- production in experimental models.

It has been thought that the stimulation of adenosine A2 receptors activates adenylate cyclase in the coronary arteries to produce cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and relaxes coronary vascular smooth muscle.

Increases in cAMP may increase the uptake of Ca2 into the sarcoplasmic reticulum and cause vasorelaxation.

Furthermore, cyclic AMP may open KATP channels and decrease Ca2 movement inward into smooth muscle cells. Indeed, adenosine-induced coronary vasodilation is attenuated by glibenclamide, an inhibitor of KATP channels (46).

In the ischemic heart, thromboembolism in small coronary arteries, which is believed to be one of the causes of the ‘‘no reflow phenomenon’’ of the reperfused myocardium, may worsen the severity of acute myocardial infarction.

Small coronary microembolizations are caused by platelet aggregation, and stimulation of adenosine A2 receptors has been reported to inhibit the platelet aggregation induced by norepinephrine in vitro (47, 48).

We have investigated whether endogenous adenosine inhibits thromboembolism secondary to platelet aggregation in in vivo ischemic hearts (Fig. 6) (47).

We further examined the cellular mechanisms of platelet aggregation when adenosine receptors are inhibited (Fig. 6).

The appearance of P-selectin in the platelet increased 8-(sulfophenyl)theophylline treatment, and the inhibitor of P-selectin inhibited platelet aggregation with leukocytes, and thus with endothelial cells (48).

Thus, endogenous adenosine released in the ischemic myocardium inhibited the activation of platelet P-selectin and inhibited microembolization in small coronary vessels.

Adenosine also inhibits leukocyte chemotaxis (49) and the production of oxygen-derived free radicals through the stimulation of adenosine A2 receptors.

This decrease in the inflammatory response may also be cardioprotective.

Interestingly, the activation of leukocytes decreases ecto-5’-nucleotidase activity (50), which may decrease adenosine production and activate leukocytes further.

These vicious cycles in leukocytes may enhance the injury in ischemic hearts by the release of oxygen-derived free radicals and adhesion to endothelial cells to obstruct small coronary arteries.

2. Nitric Oxide

Nitric oxide (NO) activates soluble guanylate cyclase and increases cyclic GMP levels.

Increases in cGMP cause several cardiovascular actions.

NO relaxes smooth muscles, inhibits platelet aggregation, inhibits the activation of leukocytes, attenuates myocardial contraction, attenuates the presynaptic release of norepinephrine, and inactivates the renin–angiotensin system.

NO also attenuates the expression of adhesion molecules.

These actions of NO are very similar to those of adenosine, although the cellular signal transduction is different.

NO is believed to attenuate ischemia and reperfusion injury as does adenosine.

Although NO with oxygen radicals produces peroxymitrite, and peroxymitrite is very harmful to the cells, the consensus is that NO is beneficial to ischemia and reperfusion injury as a whole because the beneficial actions of NO may overcome the deleterious pathway of peroxymitrite.

3. ANP and BNP

Both ANP and BNP are released from the atrium and ventricle of the heart, which may play an important role in the homeostasis of the cardiovascular system (51).

Both ANP and BNP activate particulate guanylate cyclase and increase cellular cyclic GMP levels.

ANP and BNP regulate coronary vascular tone. ANP is increased in patients with chronic heart failure, chronic renal failure, systemic hypertension, and paroxysmal artial tachycardia.

However, there is no clear consensus whether ANP is involved in the ischemic myocardium.

Interestingly and importantly, when ANP was infused into the canine ischemic myocardium, we found that coronary blood flow increases and myocardial contractile and metabolic function recover in canine ischemic hearts.

Furthermore, we found that ANP attenuates myocardial necrosis following 90 min of ischemia and 6 hr of reperfusion in open chest dogs.

BNP is also increased in the mechanically stressed heart.

These data support that either ANP or BNP is cardioprotective against ischemia and reperfusion injury. Of course, ANP and BNP reduce blood volume by increasing urine output and decrease heart size, which mainly favor cardioprotection.

There are no clear data whether ANP or BNP affects leukocytes or platelets to reduce myocardial damage further.

4. Acidosis

Cellular acidosis is thought to be a natural defense mechanism against myocardial ischemia and reperfusion injury.

H blocks Ca2 channels and Na/Ca2 exchange and antagonizes Ca2 overload in the myocardium (30, 31).

Furthermore, H increases NO and adenosine production of ischemic myocardium.

Indeed, data show that transient cellular acidosis attenuates reperfusion injury, restores myocardial function, and limits cellular necrosis (30, 31).

These results indicate that acidosis is a self-protecting mechanism and that the moderate enhancement of cellular acidosis may induce cardioprotection against ischemia and reperfusion injury.

5. Endothelium-Derived Hyperpolarizing Factor (EDHF)

Endothelial cells produce not only nitric oxide, but also the substance that decreases the membrane potential, i.e. endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor.

EDHF decreases membrane potentials and causes relaxation of the vessels.

EDHF has not been identified yet, but (1) bradykinin is thought to increase EDHF levels and (2) EDHF opens Ca2 activated K (KCa) channels.

The inhibitor of KCa channels decreases coronary blood flow and worsens the contractile and metabolic functions of ischemic myocardium and EDHF, or the opening of KCa channels, plays an important role in the regulation of coronary blood flow in the ischemic myocardium (52).

Furthermore, the opening of KCa channels induces an infarct size-limiting effect (53).

3) How to mediate Cardioprotection during Ischemia and Reperfusion

Expand

The potential treatment of acute myocardial infarction is to reperfuse the occluded coronary artery.

Either percutaneus transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) or percutaneous transluminal coronary recanalization (PTCR) is recognized to be the most effective treatment of acute myocardial infarction in clinical settings.

However, our impression is that either PTCA or PTCR limits ischemia and reperfusion injury to a modest extent because of the diminution of a beneficial effect by reperfusion injury, and we need to find the adjunctive therapy to treat ischemia and reperfusion injury directly.

Because many factors are involved in ischemia and reperfusion injury, the idea is (1) to use many drugs that inhibit each deleterious factor or (2) to use one drug that inhibits many deleterious factors.

The latter seems to be more plausible for clinical settings.

The candidates are adenosine, NO, and ANP for treatment.

Because adenosine also attenuates reversible and irreversible myocardial cellular injury after reperfusion in various species of animals, intracoronary infusion of adenosine results in a 75% reduction in myocardial infarct size in dogs (54) and attenuates contractile dysfunction in rats.

The AMISTAD trial reveals that adenosine administration is effective for the treatment of acute myocardial infarction (55), and we are also planning an ATP administration trial for patients with acute myocardial infarction (COAT trial) (56).

Adenosine-related compounds may be effective for cardioprotection against ischemia and reperfusion injury. Vesnarinone, a new inotropic agent, has been reported to inhibit adenosine uptake in immune cells (57), which was also demonstrated in myocytes, endothelial cells, and smooth muscle cells (58).

Furthermore, we also observed that vesnarinone activates ecto-5’-nucleotidase via protein kinase C-independent mechanisms.

These data suggest that vesnarinone may be effective for acute myocardial infarction. When testing this hypothesis, we observed that vesnarinone limits infarct size, an effect which is blunted by an antagonist of adenosine receptors (59).

Furthermore, both methotrexate and sulfasarazine, drugs for rheumatoid arthritis, are reported to attenuate inflammation via adenosine and ecto-5’-nucleotidase (60).

We also tested whether a methotrexate analogue mediates cardioprotection.

We found that a methotrexate analogue mediates an infarct size-limiting effect, which is completely abolished by either an antagonist of adenosine receptors or AOPCP (unpublished data).

AICA riboside also increased the activity of ecto-5’- nucleotidase, which may have merit for cardioprotection.

Enhancement of nitric oxide or ANP/BNP may be another tool used to attenuate ischemia and reperfusion injury.

Indeed, the V-Heft I trial reveals that nitrate, the NO donor, is effective for the treatment of chronic heart failure.

Furthermore, ACE inhibitors, which are used in the treatment of ischemic or nonischemic chronic heart failure, are reported to increase cardiac NO levels via bradykinin-dependent mechanisms in experimental and clinical studies.

We have proved that either cilazapril or imidaprilat increases cardiac NO levels and attenuates the severity of myocardial ischemia via a NO-dependent pathway.

Nipradilol can be used for the NO donor with the additional effects of β-adrenoceptor blockade, which may be useful compared to ordinary NO donors or β-adrenoceptor blockers.

ANP is available for the treatment of heart failure, although it is difficult to use ANP for the treatment of chronic heat failure because there is only an intravenous type of ANP.

Candoxiatril, which inhibits the degradation of ANP, has been developed and can be used for the treatment of chronic heart failure.

4) Treatments after Acute Myocardial Infarction

A. Pharmacological Approach

Expand

Chronic heart failure, the end state of the ischemic heart, is characterized by the reduction of cardiac performance relative to the oxygen demand of the body; however, several neurohormonal factors have been reported to exacerbate the severity of chronic heart failure.

Catecholamine, renin–angiotensin, and cytokines may be involved in the pathophysiology of chronic heart failure.

Indeed, chronic heart failure is treated effectively by β-adrenoceptor antagonists and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (61, 62), and these drugs have been proven to be effective in the treatment of chronic heart failure in mass studies. Carvedilol is reported to be more effective than ordinary β-adrenoceptor blockers (63).

Because carvedilol is characterized as a β-adrenoceptor-blocking agent with modest -adrenoceptor blocking capability, one may argue that the vasodilatory capability of 1-adrenoceptor blockade may be effective in the β-blockaded condition, as the β- blocker decreases cardiac output, but 1-adrenoceptor blockade may compensate to maintain cardiac output.

However, prazosin has not been proven to be effective for the treatment of chronic heart failure, suggesting that 1-adrenoceptor blockade does not explain the beneficial effect of carvedilol.

Carvedilol has an antioxidant effect. This effect may be important, as oxidative stress has been implicated in the pathophysiology of chronic heart failure.

How about adenosine or NO? Adenosine and NO are reported to decrease sympathetic tone and activity of the renin–angiotensin and the cytokine systems, and NO has been proven to be effective in the treatment of chronic heart failure.

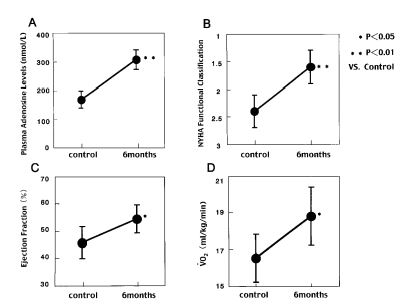

Interestingly, we observed that the plasma adenosine levels increased according to NYHA classification in patients with chronic heart failure (64).

Furthermore, when we administered dipyridamole or dilazep (Fig. 7 and 8) to patients with chronic heart failure for 6 months, ventricular wall motion and exercise capacity in these patients were increased (65).

Therefore, adenosine may be an alternative treatment of chronic heart failure.

Endothelin receptor antagonists are also effective in the treatment of chronic heart failure and have been tested in clinical trials.

B. Molecular Approach

Expand

Other strategies for the treatment of chronic heart failure are to compensate for the loss of myocardium and to decrease myocardial fibrosis.

Genes to change mature cardiomyocytes to myoblasts with proliferative capability have not yet been identified.

It is difficult to reproduce cardiomyocytes from the myoblasts in vivo at present.

However, many molecular investigators are focusing on finding the master gene to regulate the proliferative capability of cardiomyocytes.

In the future, the proliferation of cardiomyocytes will be one of the treatments of chronic heart failure.

Another method that could potentially be used to restore the volume and numbers of cardiomyocytes is the transplantation of cardiomyocytes.

Because human embryonic stem (ES) cells are available, if we find a way to change ES cells to cardiomyocytes, we can transplant the cardiomyocytes to failing hearts.

Indeed, transfection of Flk genes changes ES cells to endothelial cells (9), suggesting that the transfection of cardiomoycytespecific genes may cause changes in morphogenesis to cardiomyocytes.

Furthermore, when human ES cells are transplanted into leg muscles of mice, teratomas form in which human ES cells can be transformed into various human tissues and cells (66) (Fig. 9), suggesting that the analysis of teratoma may give a hint to the methods of how ES cells become cardiomyocytes.

These issues need further investigation.

C. Mechanical Approach

Expand

Another fascinating approach for the treatment of chronic heart failure is the artificial heart.

Although heart transplantation is used all over the world, the number of donor hearts is not sufficient to treat all of the patients with chronic heart failure.

Therefore, it is important to develop artificial hearts for the treatment of chronic heart failure.

In the clinical setting, the left ventricular assist device is available to support failing hearts.

5) Future Directions of Investigation of Cardioprotection

Expand

Because many factors that cause deterioration of the function and metabolism of the heart are activated in ischemic hearts, it is important to recognize and inhibit the multiple deleterious factors.

One strategy of pharmacological interventions is to administer corresponding drugs to attenuate the multiple deleterious factors, e.g., superoxide dismutase for oxygen-derived free radicals.

However, this strategy is not realistic in the clinical setting because this strategy requires the administration of many drugs to attenuate multiple deleterious factors.

Another possibility is to administer one substance that has multiplicity of action. The candidate is adenosine or nitric oxide.

Two other directions are gene therapy and artificial organs, although these two strategies have not been investigated thoroughly.

If human cardiomyocytes are cultured in the test tube and are transplanted to failing hearts, this method may become a potential treatment for the failing heart, although we need to elucidate how coronary vascular systems and extracellular matrix systems are incorporated to support myocardial cells.

These three directions, i.e., pharmacological interventions, gene interventions, and artificial interventions, may synergistically mediate cardioprotection for failing hearts.

6) Summary

Expand

Both prevention and attenuation of ischemia and reperfusion injury in patients with acute coronary syndromes are critically important for cardiologists.

To save these patients from deleterious ischemic damages, there are three different strategies.

The first strategy is to increase ischemic tolerance before the onset of myocardial ischemia.

Prevention of plaque rupture comes first; HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors such as pravastatin may attenuate plaque rupture.

Growth factors can induce collateral circulation to prevent or attenuate the ischemic damages.

Finding the trigger mechanisms of the infarct size-limiting effect of ischemic preconditioning is important in inducing ischemic tolerance in advance.

The second strategy is to attenuate ischemia and reperfusion injury when the irreversible process of myocardial cellular injury occurs.

Pharmacological interventions, such as adenosine or nitric oxide, may contribute to attenuate the ischemic damages.

The third strategy is to treat ischemic chronic heart failure that is caused after acute myocardial infarction. Gene therapy or the development of artificial hearts may provide a potential treatment in chronic failing hearts.

Taken together, we need to investigate potential mechanisms of the cellular damages and the tools for cardioprotection before, during, and after the onset of acute myocardial infarction.

7) References

Expand

Sacks, F. M., Pfeffer, M. A., Moye, L. A., Rouleau, J. L., Rutherford, J. D., Cole, T. G., Brown, L., Warnica, J. W., Arnold, J. M., Wun, C. C., Davis, B. R., and Braunwald, E. N. (1996). The effect of pravastatin on coronary events after myocardial infarction in patients with average cholesterol levels: For cholesterol and recurrent events trial investigators. N Engl. J. Med. 335, 1001–1009.

Casscells, W., Hathorn, B., David, M., Krabach, T., Vaughn, W. K., McAllister, H. A., Bearman, G., and Willerson, J. T. (1996). Thermal detection of cellular infiltrates in living atherosclerotic plaques: possible implications for plaque rupture and thrombosis. Lancet 347, 1447–1451.

Watanabe, E., Smith, D. M., Sun, J., Smart, F. W., Delcarpio, J. B., Roberts, T. B., Van Meter, C. H., Jr., and Claycomb, W. C. (1998). Effect of basic fibroblast growth factor on angiogenesis in the infarcted porcine heart. Basic Res. Cardiol. 93, 30–37.

Schaper, W. (1991). Angiogenesis in the adult heart. Basic Res. Cardiol. 86, Suppl 2, 51–56.

Losordo, D. W., Vale, P. R., Symes, J. F., Dunnington, C. H., Esakof, D. D., Maysky, M., Ashare, A. B., Lathi, K., and Isner, J. M. (1998). Gene therapy for myocardial angiogenesis: Initial clinical results with direct myocardial injection of phVEGF165 as sole therapy for myocardial ischemia. Circulation 98, 2800–2804.

Yanagisawa, M. A., Uchida, Y., Nakamura, F., Tomaru, T., Kido, H., Kamijo, T., Sugimoto, T., Kaji, K., Utsuyama, M., Kurashima, C., and Ito, H. (1992). Salvage of infarcted myocardium by angiogenic action of basic fibroblast growth factor. Science 257, 1401– 1403.

Abramovitch, R., Neeman, M., Reich, R., Stein, I., Keshet, E., Abraham, J., Solomon, A., and Marikovsky, M. (1998). Intercellular communication between vascular smooth muscle and endothelial cells mediated by heparin-binding epidermal growth factorlike growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor. FEBS Lett. 425, 441–447.

Sasayama, S., and Fujita, M. (1992). Recent insights into coronary collateral circulation. Circulation 85, 1197–1204.

Hirashima, M., Kataoka, H., Nishikawa, S., Matsuyoshi, N., Nishikawa, S. I. (1999). Maturation of embryonic stem cells into endothelial cells in an in vitro model of vasculogenesis. Blood 93(4), 1253–1263.

Fischer, S., Knoll, R., Renz, D., Karliczek, G. F., and Schaper, W. (1997). Role of adenosine in the hypoxic induction of vascular endothelial growth factor in porcine brain derived microvascular endothelial cells. Endothelium 5, 155–165.

Meinnger, C. J., Schelling, M. E., and Granger, H. J. (1988). Adenosine and hypoxia stimulate proliferation and migration of endothelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. 255, H554–H562.

Dusseuau, J. W., Hutchins, M., and Malbasa, D. S. (1986). Stimulation of angiogenesis by adenosine on the chick choriaoallantonic membrane. Circ. Res. 59, 163–170.

Symons, J. D., Firoozmand, E., and Longhurst, J. C. (1993). Repeated dipyridamole administration enhances collateral-dependent flow and regional function during exercise: A role for adenosine. Circ. Res. 73, 503–513.

Losardo, D. W., Vale, P. R., and Isner, J. M. (1999). Gene therapy for myocardial angiogenesis. Am Heart J. 138, 132–141.

Murry, C. E., Jennings, R. B., and Reimer, K. A. (1986). Preconditioning with ischemia: A delay of lethal cell injury in ischemic myocardium. Circulation 74, 1124–1136.

Liu, G. S., Thornton, J., Van Winkle, D. M., Stanley, A. W. H., Olsson, R. A., and Downey, J. M. (1991). Protection against infarction afforded by preconditioning is mediated by A1 adenosine receptors in rabbit heart. Circulation 84, 350–356.

Kitakaze, M., Hori, M., Morioka, T., Minamino, T., Takashima, S., Okazaki, Y., Node, K., Komamura, K., Iwakura, K., Inoue, M., and Kamada, T. (1995). 1-Adrenoceptor activation increases ectosolic 5’-nucleotidase activity and adenosine release in rat cardiomyocytes by activing protein kinase C. Circulation 91, 2226– 2234.

Kitakaze, M., Node, K., Minamino, T., Komamura, K., Funaya, H., Shinozaki, Y., Chujo, M., Mori, H., Inoue, M., Hori, M., and Kamada, T. (1996). The role of activation of protein kinase C in the infarct size-limiting effect of ischemic preconditioning through activation of ecto-5’-nucleotidase. Circulation 93, 781–791.

Tsuchida, A., Liu, Y., Liu, G. S., Cohen, M. V., and Downey, J. M. (1994). 1-Adrenergic agonists precondition rabbit ischemic

8) Other Information

9) Pathophysiology Presentation

Coronary Artery Disease

Coronary artery disease, also called coronary or atherosclerotic heart disease, is a serious condition caused by a buildup of plaque in your coronary arteries, the blood vessels that bring oxygen-rich blood to your heart. It affects millions of Americans.

Causes and Development

Plaque can start to collect along your blood vessel walls when you’re young and build up as you get older. That buildup inflames those walls and raises the risk of blood clots and heart attacks.

The plaque makes the inner walls of your blood vessels sticky. Things like inflammatory cells, lipoproteins, and calcium attach to the plaque as they travel through your bloodstream.

More of these materials build up, along with cholesterol. That pushes your artery walls out while making them narrower.

Eventually, a narrowed coronary artery may develop new blood vessels that go around the blockage to get blood to your heart muscle. But if you’re pushing yourself or stressed out, the new arteries may not be able to bring enough oxygen-rich blood to your heart.

Complications

Abnormal heart rhythm (arrhythmia), when your heartbeat loses its regular rhythm because of damage to your heart or a lack of blood supply. The most common form is called atrial fibrillation (AFib). These rhythm problems can cause heart failure or make it worse. An irregular heartbeat might lead to blood clots in your heart, and these can cause a stroke if they reach your brain.

Heart attack, when your coronary artery is totally blocked, keeping part of your heart muscle from getting enough oxygen. When blood flow to your heart muscle is blocked, your doctor might call it acute coronary syndrome.

Heart failure, when your heart becomes too weak to supply your body with the blood it needs. This can be because your heart isn’t getting enough oxygen and nutrients or it was damaged by a heart attack.

Congenital Heart Disease

“Congenital heart defect” is another way of saying your heart had a problem when you were born. You may have had a small hole in it or something more severe. Although these can be very serious conditions, many can be treated with surgery.

In some cases, doctors can find these problems during pregnancy. You might not get symptoms until adulthood, or you may not get any at all.

Causes and Development

Doctors don’t always know why a baby has a congenital heart defect. They tend to run in families.

Things that make them more likely include:

- Problems with genes or chromosomes in the child, such as Down syndrome

- Taking certain medications, or alcohol or drug abuse during pregnancy

- A viral infection, like rubella (German measles) in the mother in the first trimester of pregnancy

Types

Most congenital heart problems are structural issues like holes and leaky valves. For instance:

Heart valve defects: One may be too narrow or completely closed. That makes it hard for blood to get through. Sometimes, it can’t get through at all. In other cases, the valve might not close properly, so the blood leaks backward.

Problems with the heart’s “walls”: It could be the ones between the chambers (atria and ventricles) of your heart. Holes or passageways between the left and right side of the heart might cause blood to mix when it shouldn’t.

Issues with the heart’s muscle: These can lead to heart failure, which means the heart doesn’t pump as efficiently as it should.

Bad connections among blood vessels: In babies, this may let blood that should go to the lungs go to other parts of the body instead, or vice versa. These defects can deprive blood of oxygen and lead to organ failure.

Sudden Cardiac Death

Sudden cardiac death (SCD) is a sudden, unexpected death caused by a change in heart rhythm (sudden cardiac arrest). It is the largest cause of natural death in the U.S., causing about 325,000 adult deaths in the U.S. each year. SCD is responsible for half of all heart disease deaths.

Causes and Development

Most sudden cardiac deaths are caused by abnormal heart rhythms called arrhythmias. The most common life-threatening arrhythmia is ventricular fibrillation, which is an erratic, disorganized firing of impulses from the ventricles (the heart’s lower chambers). When this occurs, the heart is unable to pump blood and death will occur within minutes, if left untreated.

Arrhythmias

You could have an arrhythmia even if your heart is healthy. Or it could happen because you have:

- Heart disease

- The wrong balance of electrolytes (such as sodium or potassium) in your blood

- Changes in your heart muscle

- Injury from a heart attack

- Healing process after heart surgery

The many types of arrhythmias include:

Premature atrial contractions. These are early extra beats that start in the heart’s upper chambers, called the atria. They are harmless and generally don’t need treatment.

Premature ventricular contractions (PVCs). These are among the most common arrhythmias. They’re the “skipped heartbeat” we all occasionally feel. They can be related to stress or too much caffeine or nicotine. But sometimes, PVCs can be caused by heart disease or electrolyte imbalance. If you have a lot of PVCs, or symptoms linked to them, see a heart doctor (cardiologist).

Atrial fibrillation. This common irregular heart rhythm causes the upper chambers of the heart to contract abnormally.

Atrial flutter. This is an arrhythmia that’s usually more organized and regular than atrial fibrillation. It happens most often in people with heart disease and in the first week after heart surgery. It often changes to atrial fibrillation.

Paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia (PSVT). A rapid heart rate, usually with a regular rhythm, starting from above the heart’s lower chambers, or ventricles. PSVT begins and ends suddenly.

Accessory pathway tachycardias. You can get a rapid heart rate because there is an extra pathway between the heart’s upper and lower chambers. It’s just like if there was an extra road on your way home as well as your usual route, so cars can move around faster. When that happens in your heart, it can cause a fast heart rhythm, which doctors call tachycardia. The impulses that control your heart rhythm travel around the heart very quickly, making it beat unusually fast.

AV nodal reentrant tachycardia. This is another type of fast heartbeat. It’s caused by there being an extra pathway through a part of the heart called the AV node. It can cause heart palpitations, fainting, or heart failure. In some cases, you can stop it simply by breathing in and bearing down. Some drugs can also stop this heart rhythm.

Ventricular tachycardia (V-tach). A rapid heart rhythm starting from the heart’s lower chambers. Because the heart is beating too fast, it can’t fill up with enough blood. This can be a serious arrhythmia – especially in people with heart disease – and it may be linked to other symptoms.

Ventricular fibrillation. This happens when the heart’s lower chambers quiver and can’t contract or pump blood to the body. This is a medical emergency that must be treated with CPR and defibrillation as soon as possible.

Long QT syndrome. This may cause potentially dangerous arrhythmias and sudden death. Doctors can treat it with medications or devices called defibrillators.

Bradyarrhythmias. These are slow heart rhythms, which may be due to disease in the heart’s electrical system. When this occurs, you may feel like you are going to pass out, or actually pass out. This could also be from medication. The treatment for this could be a pacemaker.

Sinus node dysfunction. This slow heart rhythm is due to a problem with the heart’s sinus node. Some people with this type of arrhythmia need a pacemaker.

Heart block. There is a delay or a complete block of the electrical impulse as it travels from the heart’s sinus node to its lower chambers. The heart may beat irregularly and, often, more slowly. In serious cases, you’d get a pacemaker.

Pericarditis

Pericardial disease, or pericarditis, is inflammation of any of the layers of the pericardium. The pericardium is a thin tissue sac that surrounds the heart and consists of:

- Visceral pericardium – an inner layer that envelopes the entire heart

- A middle fluid layer to prevent friction between the visceral pericardium and parietal pericardium

- Parietal pericardium – an outer layer made of fibrous tissue

Causes and Development

Causes of pericarditis include:

- Infections

- Heart surgery

- Heart attack

- Trauma

- Tumors

- Cancer

- Radiation

- Autoimmune diseases (such as rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, or scleroderma)

- For some people, no cause can be found.

Pericarditis can be acute (occurring suddenly) or chronic (long-standing).

Constrictive Pericarditis

Constrictive pericarditis occurs when the pericardium becomes thickened and scarred. This can make it difficult for the heart to expand with blood.