Joints of the Lower Limb

The Hip Joint

Expand

The hip joint is a ball and socket synovial joint, formed by an articulation between the pelvic acetabulum and the head of the femur.

It forms a connection from the lower limb to the pelvic girdle, and thus is designed for stability and weight-bearing – rather than a large range of movement.

Structures of the Hip Joint

Expand

Articulating Surfaces

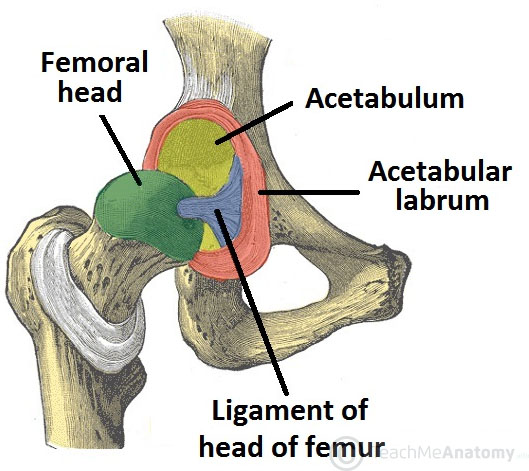

The hip joint consists of an articulation between the head of femur and acetabulum of the pelvis.

The acetabulum is a cup-like depression located on the inferolateral aspect of the pelvis. Its cavity is deepened by the presence of a fibrocartilaginous collar – the acetabular labrum. The head of femur is hemispherical, and fits completely into the concavity of the acetabulum.

Both the acetabulum and head of femur are covered in articular cartilage, which is thicker at the places of weight bearing.

The capsule of the hip joint attaches to the edge of the acetabulum proximally. Distally, it attaches to the intertrochanteric line anteriorly and the femoral neck posteriorly.

Ligaments

Expand

The ligaments of the hip joint act to increase stability. They can be divided into two groups – intracapsular and extracapsular:

Intracapsular

The only intracapsular ligament is the ligament of head of femur. It is a relatively small structure, which runs from the acetabular fossa to the fovea of the femur.

It encloses a branch of the obturator artery (artery to head of femur), a minor source of arterial supply to the hip joint.

Extracapsular

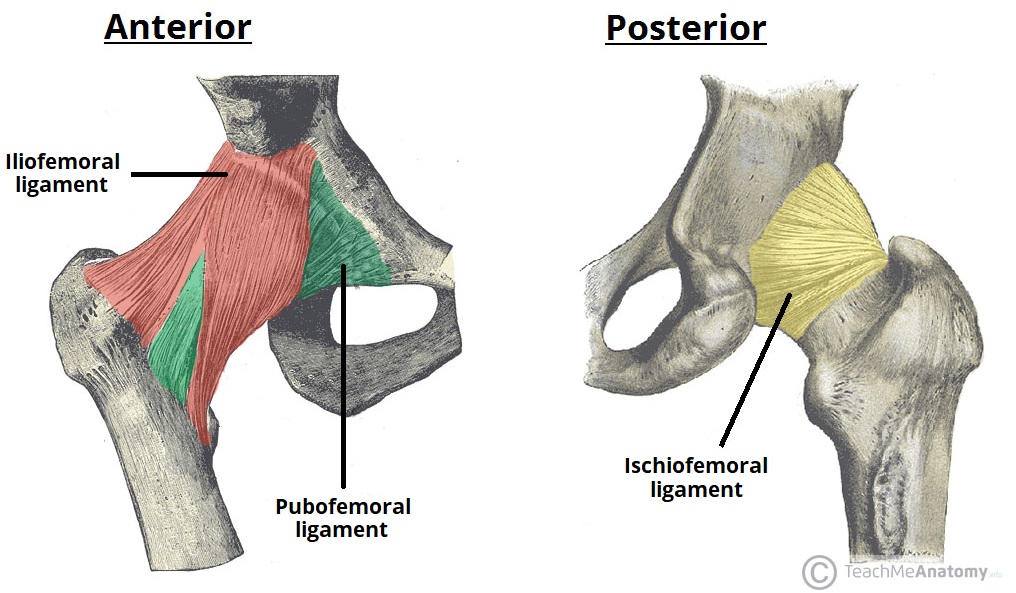

There are three main extracapsular ligaments, continuous with the outer surface of the hip joint capsule:

Iliofemoral ligament – arises from the anterior inferior iliac spine and then bifurcates before inserting into the intertrochanteric line of the femur. It has a ‘Y’ shaped appearance, and prevents hyperextension of the hip joint. It is the strongest of the three ligaments. Pubofemoral – spans between the superior pubic rami and the intertrochanteric line of the femur, reinforcing the capsule anteriorly and inferiorly. It has a triangular shape, and prevents excessive abduction and extension. Ischiofemoral– spans between the body of the ischium and the greater trochanter of the femur, reinforcing the capsule posteriorly. It has a spiral orientation, and prevents hyperextension and holds the femoral head in the acetabulum.

Neurovascular Supply

Expand

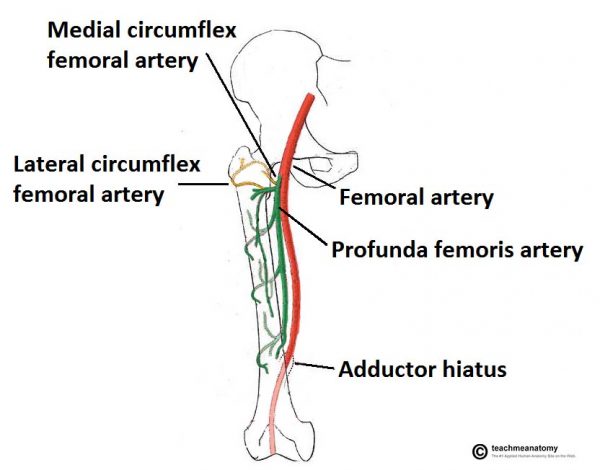

The arterial supply to the hip joint is largely via the medial and lateral circumflex femoral arteries – branches of the profunda femoris artery (deep femoral artery). They anastomose at the base of the femoral neck to form a ring, from which smaller arteries arise to supply the hip joint itself.

The medial circumflex femoral artery is responsible for the majority of the arterial supply (the lateral circumflex femoral artery has to penetrate through the thick iliofemoral ligament). Damage to the medial circumflex femoral artery can result in avascular necrosis of the femoral head.

The artery to head of femur and the superior/inferior gluteal arteries provide some additional supply.

The hip joint is innervated primarily by the sciatic, femoral and obturator nerves. These same nerves innervate the knee, which explains why pain can be referred to the knee from the hip and vice versa.

Stabilising Factors

Expand

The primary function of the hip joint is to weight-bear. There are a number of factors that act to increase stability of the joint.

The first structure is the acetabulum. It is deep, and encompasses nearly all of the head of the femur. This decreases the probability of the head slipping out of the acetabulum (dislocation).

There is a horseshoe shaped fibrocartilaginous ring around the acetabulum which increases its depth, known as the acetabular labrum. The increase in depth provides a larger articular surface, further improving the stability of the joint.

The iliofemoral, pubofemoral and ischiofemoral ligaments are very strong, and along with the thickened joint capsule, provide a large degree of stability. These ligaments have a unique spiral orientation; this causes them to become tighter when the joint is extended.

In addition, the muscles and ligaments work in a reciprocal fashion at the hip joint:

Anteriorly, where the ligaments are strongest, the medial flexors (located anteriorly) are fewer and weaker.

Posteriorly, where the ligaments are weakest, the medial rotators are greater in number and stronger – they effectively ‘pull’ the head of the femur into the acetabulum.

Movements and Muscles

Expand

The movements that can be carried out at the hip joint are listed below, along with the principle muscles responsible for each action:

- Flexion – iliopsoas, rectus femoris, sartorius, pectineus

- Extension – gluteus maximus; semimembranosus, semitendinosus and biceps femoris (the hamstrings)

- Abduction – gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, piriformis and tensor fascia latae

- Adduction – adductors longus, brevis and magnus, pectineus and gracilis

- Lateral rotation – biceps femoris, gluteus maximus, piriformis, assisted by the obturators, gemilli and quadratus femoris.

- Medial rotation – anterior fibres of gluteus medius and minimus, tensor fascia latae

The degree to which flexion at the hip can occur depends on whether the knee is flexed – this relaxes the hamstring muscles, and increases the range of flexion.

Extension at the hip joint is limited by the joint capsule and the iliofemoral ligament. These structures become taut during extension to limit further movement.

The Knee Joint

Expand

The knee joint is a hinge type synovial joint, which mainly allows for flexion and extension (and a small degree of medial and lateral rotation). It is formed by articulations between the patella, femur and tibia.

Articulating Surfaces

Expand

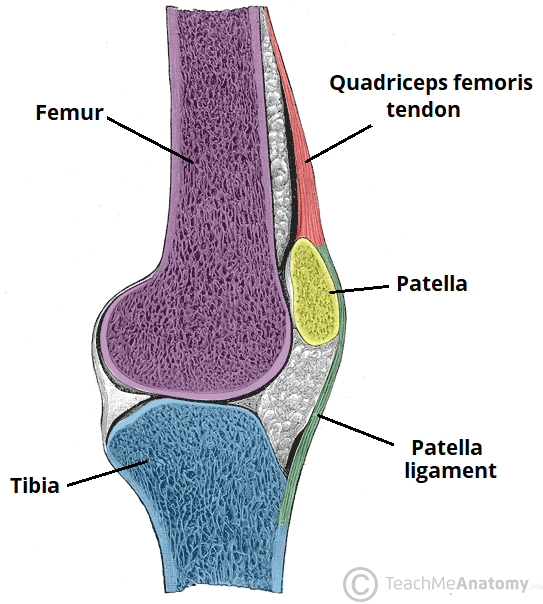

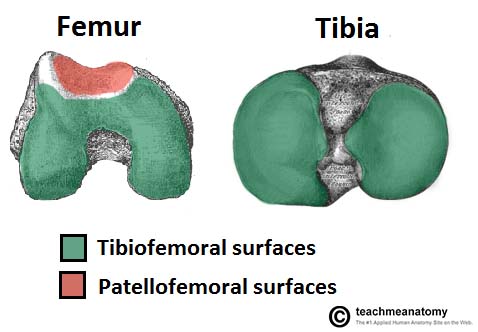

The knee joint consists of two articulations – tibiofemoral and patellofemoral. The joint surfaces are lined with hyaline cartilage, and are enclosed within a single joint cavity.

Tibiofemoral – medial and lateral condyles of the femur articulate with the tibial condyles. It is the weight-bearing component of the knee joint.

Patellofemoral – anterior aspect of the distal femur articulates with the patella. It allows the tendon of the quadriceps femoris (knee extensor) to be inserted directly over the knee – increasing the efficiency of the muscle.

As the patella is both formed and resides within the quadriceps femoris tendon, it provides a fulcrum to increase power of the knee extensor, and serves as a stabilising structure that reduces frictional forces placed on femoral condyles.

Neurovasculature

Expand

The blood supply to the knee joint is through the genicular anastomoses around the knee, which are supplied by the genicular branches of the femoral and popliteal arteries.

The nerve supply, according to Hilton’s law, is by the nerves which supply the muscles which cross the joint. These are the femoral, tibial and common fibular nerves.

Menisci

Expand

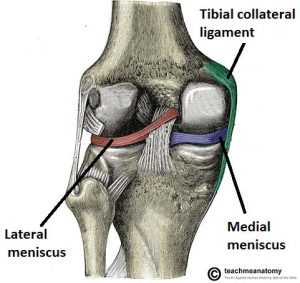

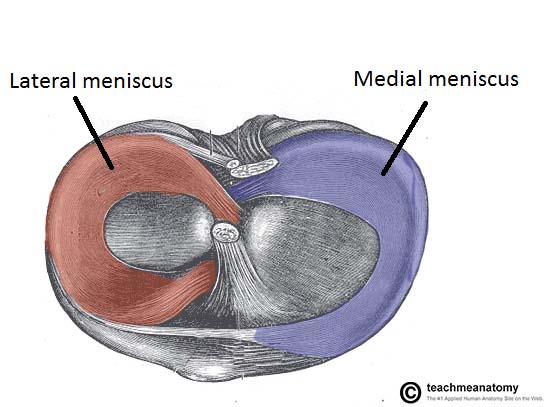

The medial and lateral menisci are fibrocartilage structures in the knee that serve two functions:

To deepen the articular surface of the tibia, thus increasing stability of the joint.

To act as shock absorbers by increasing surface area to further dissipate forces.

They are C shaped, and attached at both ends to the intercondylar area of the tibia.

In addition to the intercondylar attachment, the medial meniscus is fixed to the tibial collateral ligament and the joint capsule. Damage to the tibial collateral ligament usually results in a medial meniscal tear.

The lateral meniscus is smaller and does not have any extra attachments, rendering it fairly mobile.

Bursae

Expand

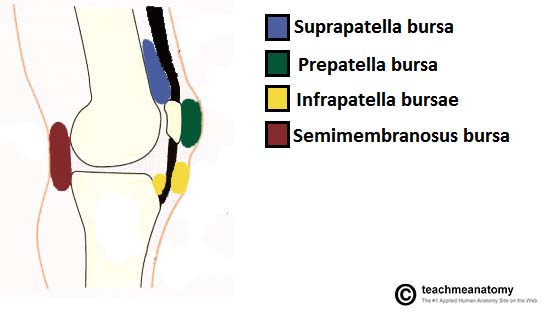

A bursa is synovial fluid filled sac, found between moving structures in a joint – with the aim of reducing wear and tear on those structures. There are four bursae found in the knee joint.

Suprapatella bursa – This is an extension of the synovial cavity of the knee, located between the quadriceps femoris and the femur.

Prepatella bursa – Found between the apex of the patella and the skin.

Infrapatella bursa – Split into deep and superficial. The deep bursa lies between the tibia and the patella ligament. The superficial lies between the patella ligament and the skin.

Semimembranosus bursa – Located posteriorly in the knee joint, between the semimembranosus muscle and the medial head of the gastrocnemius.

Ligaments

Expand

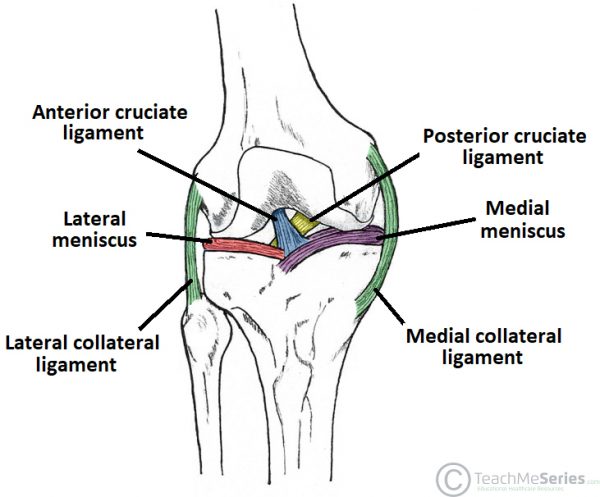

The major ligaments in the knee joint are:

Patellar ligament– a continuation of the quadriceps femoris tendon distal to the patella. It attaches to the tibial tuberosity.

Collateral ligaments– two strap-like ligaments. They act to stabilise the hinge motion of the knee, preventing excessive medial or lateral movement

Tibial (medial) collateral ligament – A wide and flat ligament, found on the medial side of the joint. Proximally, it attaches to the medial epicondyle of the femur, distally it attaches to the medial condyle of the tibia.

Fibular (lateral) collateral ligament – Thinner and rounder than the tibial collateral, this attaches proximally to the lateral epicondyle of the femur, distally it attaches to a depression on the lateral surface of the fibular head.

Cruciate Ligaments– These two ligaments connect the femur and the tibia. In doing so, they cross each other, hence the term ‘cruciate’ (Latin for like a cross)

Anterior cruciate ligament– it attaches at the anterior intercondylar region of the tibia where it blends with the medial meniscus. It ascends posteriorly to attach to the femur in the intercondylar fossa. It prevents anterior dislocation of the tibia onto the femur.

Posterior cruciate ligament– attaches at the posterior intercondylar region of the tibia, and ascends anteriorly to attach to the anteromedial femoral condyle. It prevents posterior dislocation of the tibia onto the femur.

Movements

Expand

There are four main movements that the knee joint permits:

Extension: Produced by the quadriceps femoris, which inserts into the tibial tuberosity.

Flexion: Produced by the hamstrings, gracilis, sartorius and popliteus.

Lateral rotation: Produced by the biceps femoris.

Medial rotation: Produced by five muscles; semimembranosus, semitendinosus, gracilis, sartorius and popliteus.

Lateral and medial rotation can only occur when the knee is flexed (if the knee is not flexed, the medial/lateral rotation occurs at the hip joint).

Tibiofibular Joints

Expand

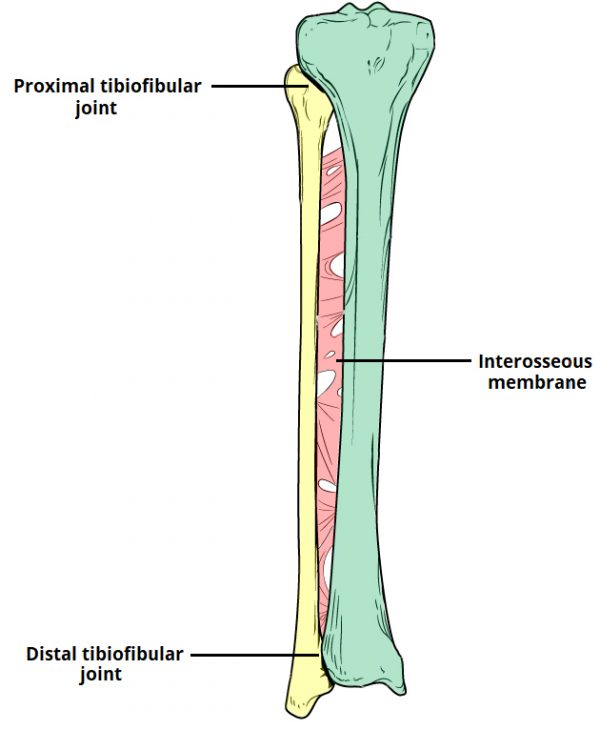

The proximal and distal tibiofibular joints refer to two articulations between the tibia and fibula of the leg. These joints have minimal function in terms of movement but play a greater role in stability and weight-bearing.

Proximal Tibiofibular Joint

Expand

Articulating Surfaces

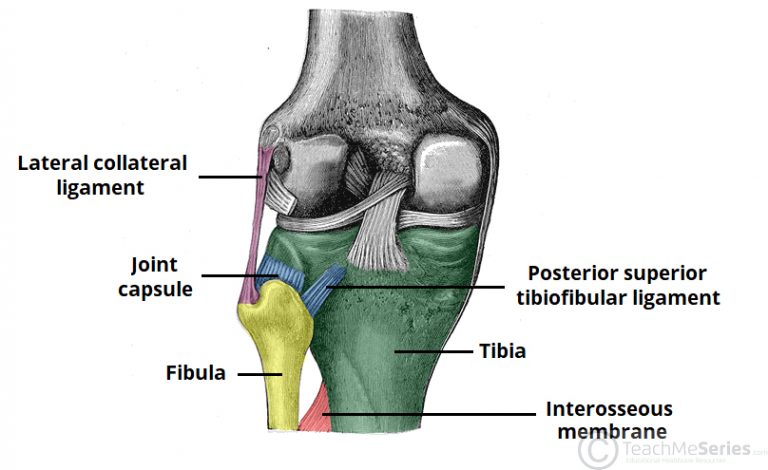

The proximal tibiofibular joint is formed by an articulation between the head of the fibula and the lateral condyle of the tibia.

It is a plane type synovial joint; where the bones to glide over one another to create movement.

Supporting Structures

The articular surfaces of the proximal tibiofibular joint are lined with hyaline cartilage and contained within a joint capsule.

The joint capsule receives additional support from:

Anterior and posterior superior tibiofibular ligaments – span between the fibular head and lateral tibial condyle

Lateral collateral ligament of the knee joint

Biceps femoris – provides reinforcement as it inserts onto the fibular head.

Neurovascular Supply

The arterial supply to the proximal tibiofibular joint is via the inferior genicular arteries and the anterior tibial recurrent arteries.

The joint is innervated by branches of the common fibular nerve and the nerve to the popliteus (a branch of the tibial nerve).

Distal Tibiofibular joint

Expand

Articulating Surfaces

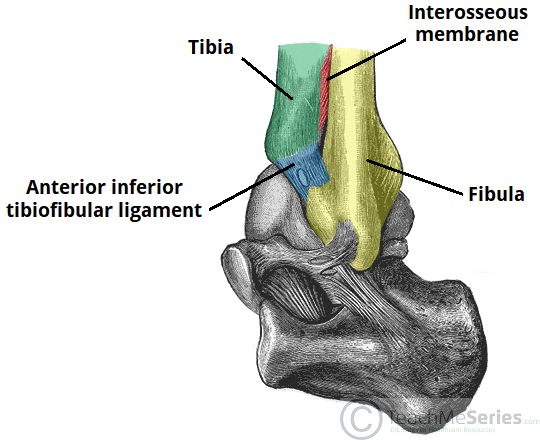

The distal (inferior) tibiofibular joint consists of an articulation between the fibular notch of the distal tibia and the fibula.

It is an example of a fibrous joint, where the joint surfaces are by bound by tough, fibrous tissue.

Supporting Structures

The distal tibiofibular joint is supported by:

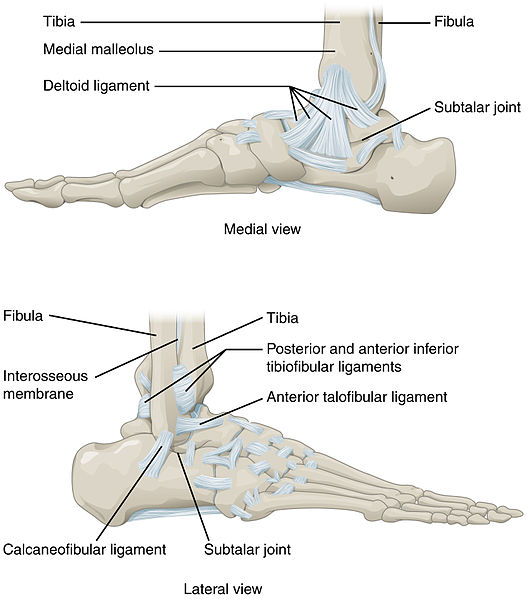

- Interosseous membrane – a fibrous structure spanning the length of the tibia and fibula.

- Anterior and posterior inferior tibiofibular ligaments

- Inferior transverse tibiofibular ligament – a continuation of the posterior inferior tibiofibular ligament.

As it is a fibrous joint, the distal tibiofibular joint does not have a joint capsule (only synovial joints have a joint capsule).

Neurovascular Supply

Expand

Arterial supply to the distal tibiofibular joint is via branches of the fibular artery and the anterior and posterior tibial arteries.

The nerve supply is derived from the deep peroneal and tibial nerves.

The Ankle Joint

Expand

The ankle joint (or talocrural joint) is a synovial joint located in the lower limb. It is formed by the bones of the leg (tibia and fibula) and the foot (talus).

Functionally, it is a hinge type joint, permitting dorsiflexion and plantarflexion of the foot.

Articulating Surfaces

Expand

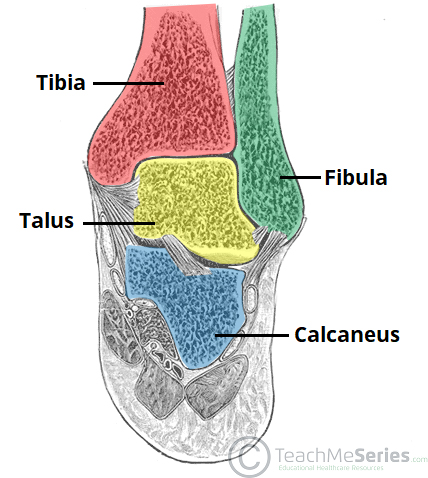

The ankle joint is formed by three bones; the tibia and fibula of the leg, and the talus of the foot:

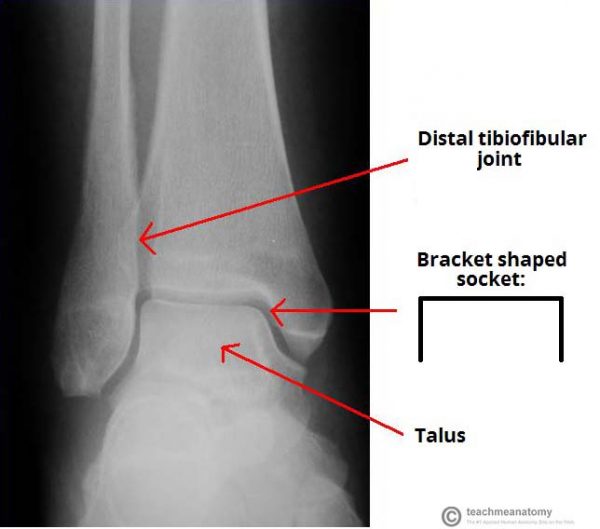

The tibia and fibula are bound together by strong tibiofibular ligaments. Together, they form a bracket shaped socket, covered in hyaline cartilage. This socket is known as a mortise.

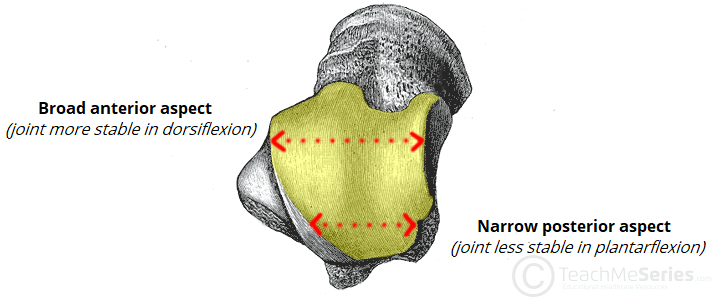

The body of the talus fits snugly into the mortise formed by the bones of the leg. The articulating part of the talus is wedge shaped – it is broad anteriorly, and narrow posteriorly:

- Dorsiflexion – the anterior part of the talus is held in the mortise, and the joint is more stable.

- Plantarflexion – the posterior part of the talus is held in the mortise, and the joint is less stable.

Ligaments

Expand

There are two main sets of ligaments, which originate from each malleolus.

Medial Ligament

The medial ligament (or deltoid ligament) is attached to the medial malleolus (a bony prominence projecting from the medial aspect of the distal tibia).

It consists of four ligaments, which fan out from the malleolus, attaching to the talus, calcaneus and navicular bones. The primary action of the medial ligament is to resist over-eversion of the foot.

Lateral Ligament

The lateral ligament originates from the lateral malleolus (a bony prominence projecting from the lateral aspect of the distal fibula).

It resists over-inversion of the foot, and is comprised of three distinct and separate ligaments:

- Anterior talofibular – spans between the lateral malleolus and lateral aspect of the talus.

- Posterior talofibular – spans between the lateral malleolus and the posterior aspect of the talus.

- Calcaneofibular – spans between the lateral malleolus and the calcaneus.

Movements and Muscles Involved

Expand

The ankle joint is a hinge type joint, with movement permitted in one plane.

Thus, plantarflexion and dorsiflexion are the main movements that occur at the ankle joint. Eversion and inversion are produced at the other joints of the foot, such as the subtalar joint.

- Plantarflexion – produced by the muscles in the posterior compartment of the leg (gastrocnemius, soleus, plantaris and posterior tibialis).

- Dorsiflexion – produced by the muscles in the anterior compartment of the leg (tibialis anterior, extensor hallucis longus and extensor digitorum longus).

Neurovascular Supply

Expand

The arterial supply to the ankle joint is derived from the malleolar branches of the anterior tibial, posterior tibial and fibular arteries.

Innervation is provided by tibial, superficial fibular and deep fibular nerves.

Subtalar Joint

Expand

The subtalar joint is an articulation between two of the tarsal bones in the foot – the talus and calcaneus. The joint is classed structurally as a synovial joint, and functionally as a plane synovial joint.

Articulating Surfaces

Expand

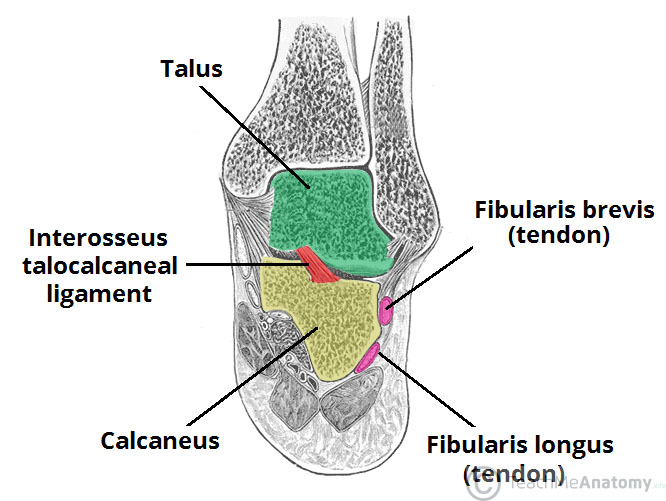

The subtalar joint is formed between two of the tarsal bones:

Inferior surface of the body of the talus – the posterior talar articular surface. Superior surface of the calcaneus – the posterior calcaneal articular facet. As is typical for a synovial joint, these surfaces are covered by articular cartilage.

Note: Some texts will refer to the talocalcaneal part of the talocalcaneonavicular joint as being part of the subtalar joint. Although this forms part of the functional joint, the true anatomical subtalar joint consists only of the surfaces mentioned above.

Stability

Expand

The subtalar joint is enclosed by a joint capsule, which is lined internally by synovial membrane and strengthened externally by a fibrous layer. The capsule is also supported by three ligaments:

- Posterior talocalcaneal ligament

- Medial talocalcaneal ligament

- Lateral talocalcaneal ligament

An additional ligament – the interosseous talocalcaneal ligament – acts to bind the talus and calcaneus together. It lies within the sinus tarsi (a small cavity between the talus and calcaneus), and is particularly strong; providing the majority of the ligamentous stability to the joint.

Movements

The subtalar joint is formed on an oblique axis and is therefore the chief site within the foot for generation of eversion and inversion movements. This movement is produced by the muscles of the lateral compartment of the leg. and tibialis anterior muscle respectively.

The nature of the articulating surface means that the subtalar joint has no role in plantar or dorsiflexion of the foot.

Neurovascular Supply

The subtalar joint receives supply from two arteries and two nerves. Arterial supply comes from the posterior tibial and fibular arteries.

Innervation to the plantar aspect of the joint is supplied by the medial or lateral plantar nerve, whereas the dorsal aspect of the joint is supplied by the deep fibular nerve.