Limb Loss

Amputation

Factors Following Limb Loss

- Physical and functional factors (adapting to enabling technology)

- Changes to appearance and body image

- Coping and adjustment

- Changes to social situation and roles

- Changes to identity and roles

- Impact on quality of life

- Environmental factors and enabling technologies

- Impact on psychological well-being (depression, anxiety, social discomfort, etc.).

Thinking Holistically

Amputation has been described as a ‘complex interaction of physical, social-demographic and psychological factors’ (Gallagher, 2004)

- Complex and unique experience leading to diversity in adjustment (Gallagher, 2004)

- To deny psychosocial perspective is denying the individual response

- Physical factors have been shown not to always predict psychosocial responses, such as depression, anxiety, activity restriction and social function (Rybarczyk et al 2004; 2009)

- Holistic approach required to recognise all factors that may influence rehabilitation and associated with ‘enhancing an outcome’ (Desmond & MacLauchlan , 2002)

Prosthetics

Advancement of Prosthetic Technology

- Scope and possibilities of prosthetics have expanded

- Improvements in quality and sophistication of prosthetics

- ‘To capitalise on the current rate of advancement in the development of prostheses and to gain a greater understanding, it is important to attend not only to the physical and technological factors which play a fundamental role, but also the social and psychosocial issues facing people who will ultimately be using the prescribed technology’ (Gallagher, 2004, page 828)

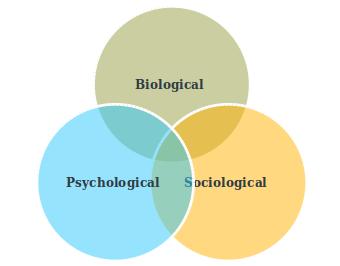

The Biopsychosocial Model

The Biopsychosocial model was developed by Engel (1980) to illustrate the interactions between biological, psychological and social factors

Argues no one factor is sufficient in understanding the complexity of health and illness

Focuses on the individual within the complex healthcare system

The Biopsychosocial Approach has been linked to the concept of ‘Person Centred Care’, which has many different definitions (Olsson, 2012).

| Biological | Psychological | Sociological |

|---|---|---|

| Level and cause of limb loss | Coping strategies | Living situation |

| Presence of co-morbidities | Adjustment | Social support |

| Pain: phantom limb /residual limb | Affective distress (i.e. depression and anxiety) | Cultural factors |

| General health | Appearance and body-image | Environment factors (enabling technology) |

| Function outcomes of prosthetic rehabilitation | Self-identity and construction of new self | Social roles |

| Expectations and motivation | Social economic factors | |

| Cognitive ability |

Varying outcomes in adjustment following an amputation

Physical issues not always impacting on psychosocial responses (Rybarczyk et al 2004; 2009)

Growing body of work exploring factors following an amputation

- Quantitative studies have identified many different factors linking to specific measures impacting on adjustment (e.g. Coffey et al 2009, Desmond & Gallagher, 2007; Atherton & Robertson)

- Qualitative studies looking at the individual experience and perception of factors impacting on their adjustment (e.g. Murray 2004, Hamill et al 2010; Oaksford et al 2005)

The experience of amputation and prosthesis use for adults

Murray & Forshaw (2013) carried out a metasynthesis of qualitative research on the experience of amputation and prosthesis use for adults

Aim to make recommendations based on the findings for clinical practice

Methods

- Research years varied within databases

- Databases: Cinahl, Medline, Web of Science

- English and peer reviewed

- Critiqued the papers using the CASP

- Included 13 studies in the results from 2001 to 2012 (total n = 216, with study samples ranging from 5 to 42)

- Mix of places such as Europe, Australia, Brazil, Taiwan and USA

Findings

- Becoming an amputee and facing prosthesis use

- Adjustment to and coping with amputation and prosthesis use

- The role of valued relationships in recovery

- Amputation and prosthesis use in social interaction

- Prosthetically enabled identities

1. Becoming an amputee and facing prosthesis use

- Variety of responses to limb loss – continuum of different emotions

- “ I felt very angry… I stopped making love to my wife… I became isolated from my colleagues and friends”

- Feelings of shock, anger, overwhelmed, vulnerable and afraid

- Impact of the reality and permanence of limb loss

Perception that family and friends could not understand

Loss of independence and control: giving up previous roles & occupations

Negative feelings coupled with a desire to build self-confidence and cope

Beliefs about the amputation: reactions and cause

Wide variations of reactions to limb loss (Desmond & MacLauchlan, 2006; Rybarzyck et al 2004; Murray & Forshaw, 2013;Unwin et al, 2009)

- Loss, grief and devastation

- Guilt

- Ambivalence

- Relief (Finding positive meaning)

- Hope

- Shock and disappointment with prosthesis

Pre-amputation decision making shown to be important (e.g. Hamill et al, 2010)

- Involved in decision making (such as timing of when it will happen, type of amputation length of residual limb)

- Appeared to help with perceptions of control and carrying out a ‘cost-benefit analysis’

Issues to think about

- Will depend on the reasons for the amputation and not always possible

- Limited options may be available

- May empower some patients, but others will prefer not to be involved (i.e. different coping styles)

2. Adjustment to and coping with amputation and prosthesis use

Adjustment often seen as similar to ‘bereavement’

Need to accept the situation

Social considerations and perceptions were instrumental in coping and adjustment

Use of ‘social comparison’

Participants recognised their own part in the adjustment process

“Disability is what you make of it… you’ve just to make the best of what you can”

Linked closely to the importance of developing a sense of optimism

Knowledge and Social comparison

Education of all aspects of new life

- Term psychoeducation (Murray 2004)

- Talking to established amputees

- Valuable source of information

- Provide positive modelling /social comparison

Social Comparison: the process of comparing ourselves with others

- Other people’s actions, behaviour and opinions are used as a yardstick against which to compare our own standing to see if we are more extreme, better, or worse

Basic Terms:

- Direction:

- upward = better off

- downward = worse off

- lateral = the same as

- Target:

- person, can be an upward, downward or lateral target

- Dimension:

- coping

- disease severity

- marital harmony

- career success, etc. (Gibbons, 1999)

Patient Expectations

Five key areas issues relating to expectations of prosthetics rehabilitation (Ostler et al 2014)

- Uncertainty

- Expectations relating to the rehabilitation service

- Personal challenges

- The prosthesis

- Returning to normality

Coping, Adjustment and Acceptance

- Optimism

- ‘There’s no point in feeling sorry for yourself, what’s the point in that , you’ve got to look on the brightside, I’ve still got a lot to look forward to’

- Perceived control over disability

- ‘You cannot let it destroy you, you have got to get the upper hand and just deal with it, conquer it, and that is what I have done, I’m a survivor’

- Positive benefits and strengthened from amputation

- ‘Sometimes I wish I could do things more quickly, but I’ve learned to be more patient, because I’ve had to basically’ (Oaksford et al. 2005)

3. The role of valued relationships in recovery

- Role of social relationships was ‘pivotal’ in the process of adjustment

- Recognised impact on families

- Importance of different dimensions of perceived social support (i.e. tangible, emotional, informative and esteem) and social networks

Perceived acceptance by others appeared to impact on sense of ‘self-worth and sense of normalcy’

Perception of a lack of supportive relationship was linked to feelings of isolation and being uncared for

Social Support

- Education of all aspects of new life

- Social support, acceptance and positive attitudes from family and friends (e.g. Gallagher & McLaughlan, 2001; Ostler et al, 2014; Marzen-Groller, 2005; Murray 2004)

- Social support, acceptance and positive attitudes from family and friends (e.g. Gallagher & McLaughlan, 2001; Ostler et al, 2014; Marzen-Groller, 2005; Murray 2004)

- Social Support

- Importance of the perception of the social support

- Different types of social support (different aspects can be important at different times)

- Maximise social support relationships and networks

4. Amputation and prosthesis use in social interaction

- Social reactions were often experience in a negative way

- perceptions of other people’s discomfort or other people avoiding contact

- Strangers often starred or asked intimate questions

- Covering up their limb loss was often an important function of wearing a prosthesis

- Wearing a prosthesis often instilled a sense of normalcy

- Tensions related to hiding limb loss

Perceptions of social discomfort and social stigma

- Being grouped as disabled and stigmatised by other, non disabled individuals has a negative effect on adjustment (Hamil et al. 2010)

- Conscious Process

- Unconscious process

- Dealing with new labels (unconscious bias?)

- Amputee!

- Diabetic Amputee!

- Feelings of shame and embarrassment about perceived ‘abnormality’ can lead to internalisation of aspect of social stigma

- Degree of social stigma related to clinical levels of depression

- Linked to perceptions of body-image and comfort

- TAPES psychosocial adjustment and self-consciousness and appearance scales (Atherton & Robertson, 2006)

5. Prosthetically enabled identities

- Prosthetic use was often linked to the label of ‘disabled’, but participants expressed the importance of being seen as an individual first

- Prosthesis use was often linked to regaining a valued identity

- Important of freedom, autonomy and mobility

- Prosthesis use led to adjustment to changes in self-identity (including self-image

Self-identity and self-image

- Self identity changes; the re-negotiation process of the new identity (Senra et al. 2011)

- Transformation of the body image and embodiment of the prosthesis (Murray & Fox 2002)

- Body-image as a system of perceptions, attitudes and beliefs about our own body

- Important part of our self-identity

- Body-image may be divided into with and without prosthesis (Mills 2003)

Adjustment following an amputation

Adjustment to amputation has therefore been described as a complex web of multiple factors

Adjustment as a final phase in the process of coping and adaptation!

Adjustment can be: - Regain status quo? - Accommodation? - Shift in perception? - A cognitive change in the way we view ourselves and the world (Sprangers and Schwartz, 1999) – links to ‘new normal’ in amputation/limb loss research

It can often be measured in terms of: - Absence of clinical level of depression, anxiety, etc.. - Quality of Life (QoL) – how to define? - Achieve new goals - Satisfaction with life - Finding meaning in life - Physical health/functioning - Activities of daily living

Stages of Adjustment

- Uncertainty

- Disruption

- Striving for recovery

- Restoration of well-being

Issues to think about

- Not all people go through stages smoothly and reach final stage

- Not all stages are experienced in the same order

- People can move back and forth between stages

- These models have been criticised for categorising patients and creating adjustment expectations (Morrison & Bennett, 2009)

Instead of stages, these models have been developed: - Control-Process Theory (Carver & Scheier, 1990) - Cognitive Adaptation Theory (Taylor, 1983)

Control-Process Theory

(Carver & Scheier, 1990)

This model is based on the premise that we ‘change’ our goals in order to take control

When goal attainment is threatened: It is suggested that: - We change or reduce our goals OR - Change expected rate of acceleration or pathway towards them

Cognitive Adaptation Theory

- Search for a meaning of the experience

- Attempting to gain a sense of control or mastery over the experience

- Making efforts to restore self-esteem (self-enhancement)

Summary

- Acknowledging the “complex interaction of physical, social-demographic and psychological factors people are confronted with following an amputation” (Gallagher, 2004)

- Importance of an holistic framework to understand all aspects of limb loss from the patient’s perspective

- Illustrates the importance of interdisciplinary work and education

- Growing body of research exploring varying psychosocial responses to amputation

- Demonstrates the important role that Occupational Therapy throughout the process of adjustment and rehabilitation

References

Atherton R. & Robertson N. (2006). Psychological adjustment to lower limb amputation amongst prosthesis users. Disabilitaty and Rehabilitation, 28, (19): 1201-9,

Callaghan B, Condie E & Johnston M. (2008). Using the common sense self-regulation model to determine psychological predictors of prostetic use and activity limitations in lower limb loss. Prostetics and Orthotics, 32 (3): 324-336

Desmond D.M. (2007) Coping, affective distress and psychosocial adjustment among people with traumatic upper limb amputations, Journal Psychosomatic Research, 62, 15-21.

Desmond D & MacLachlan M (2002). Psychological issues in prosthetic and orthotic practice: A 25 year review of psychology in Prosthetics and Orthotics International, 26, 182-188

Engel (1980). The clinical application of the biopsychosocial model. American Journal of Psychiatry, 137, 535-544.

Gallagher, P., & MacLachlan, M. (2000). Development and Psychometric evaluation of the Trinity Amputation and Prosthesis Experience Scales (TAPES). Rehabilitation Psychology, 45, 130-154.

Gallagher, P., Franchignoni, F., Giordano, A., & MacLachlan, M. (2010). Trinity Amputation and Prosthesis Experience Scales: A psychometric assessment using Classical Test Theory and Rasch Analysis (TAPES). American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 89(6): 487-496.

Gallagher P. (2004). Introduction to the special issue on psychosocial perspectives on amputation and prosthetic. Disability and Rehabilitation, 26, 827-830.

Hamil R., Carson s., & Dorahy M. (2010). Experiences of psychosocial adjustment within 18 months of amputation: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Disability and Rehabilitation, 32 (9), 729-740.

Marzen-Groller K. & Bartman K (2005). Building a successful support group for post-amputation patients. Journal of Vascular Nursing. 23 (2) 45-45.

Murray C. (2004). An interpretative phenomenological analysis of the embodiment of artificial limbs. Disability and Rehabilitation, 16, 26, 963-973.

Murray C.D. & Forshaw M.J (2013). The experience of amputation and prosthesis use for adults: a metasynthesis. Disability & Rehabilitation, 35 (14): 133-1142

Oaksford K, Frude N, & Cuddihy R. (2005). Positive coping and stress-related psychological growth following lower limb amputation. Rehabilitation Psychology. psycnet.apa.org

Ostler C. Ellis-Hill C. & Donovan-Hall M., (2014). Expectation of rehabilitation following lower limb amputation: a qualitative study. Disability and Rehabilitation, 36 (14), 1669-1175.

Unwin, J., Kacperek, L,. & Clarke, C. (2009). prospective study of positive adjustment to lower limb amputation, Clinical Rehabilitation, 2009, 23: 1044-1050.