Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Diseases

What are RMDs?

Clinical syndromes: looking for patterns

Underlying mechanism:

Inflammatory

- infection

- Automimmune

Non-Inflammatory

- Degenerative

- Traumatic

- Genetic

Tissue involved

Rheumatic diseases encompass more than 200 different diseases which span from various types of arthritis to osteoporosis and on to systemic connective tissue diseases.

This overview will focus on most commonly presented RMDs e.g. Osteoarthritis and Rheumatoid Arthritis, whilst touching upon a few others

Osteoarthritis

The word osteoarthritis is derived from the Greek word osteo which means “of the bone” arthr which means “joint” itis which means “inflammation”

It is a clinical syndrome of joint pain accompanied by varying degrees of functional limitation and reduced quality of life (NICE 2014).

Traditionally viewed as inadequate result of repair process in cartilage and degenerative/ progressive e.g.“wear and tear” (Jordan & Gracely 2013).

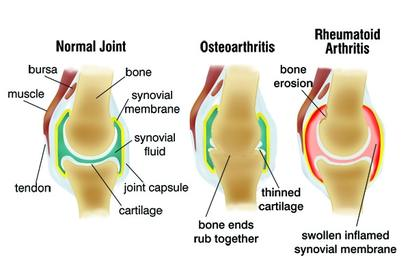

Now OA is viewed as a slow but efficient repair process that is characterised pathologically by localised loss of cartilage, remodelling of adjacent bone and associated inflammation (NICE 2014).

It involves all of the tissues of the joint and is not always progressive (Leyland et al 2012, Soni et al 2012).

When clinically evident, OA is characterized by joint pain, tenderness, limitation of movement, crepitus, occasional effusion, and variable degrees of local inflammation (Kuettner & Goldberg 1995).

In general, the diagnosis of OA can be made on clinical grounds with imaging as an additional tool (NICE 2014).

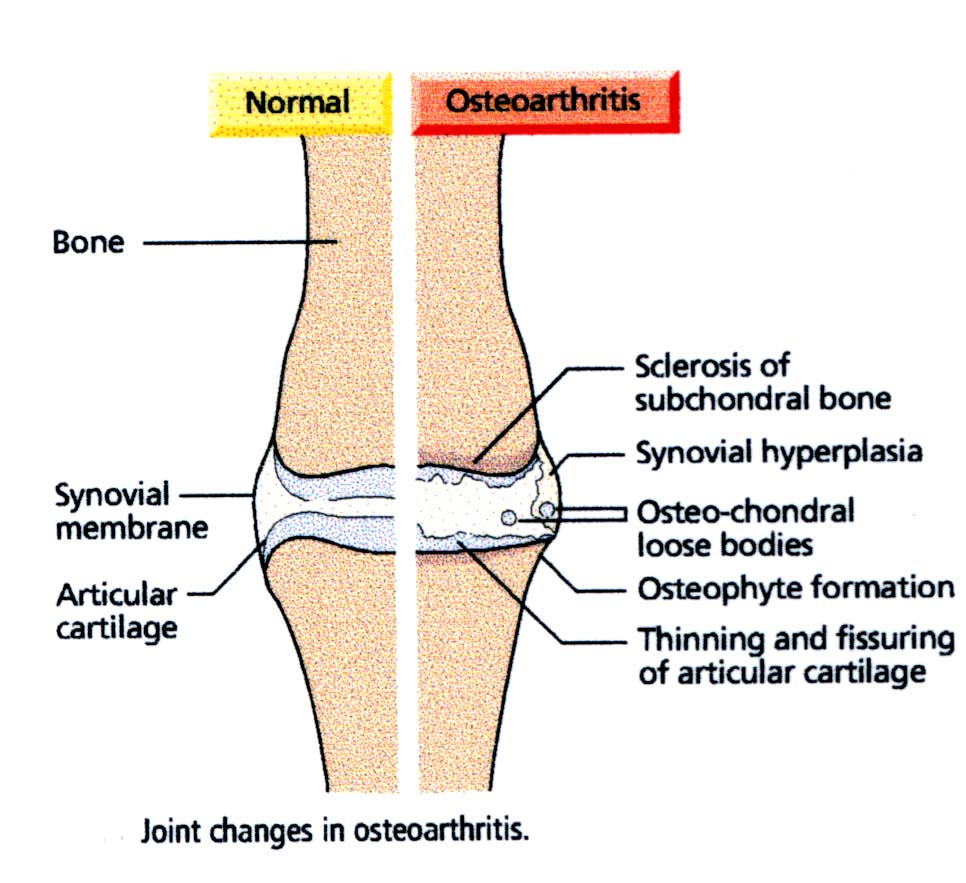

OA is characterised by damage to the articular cartilage, osteophyte formation at the joint margins, subchondral bone sclerosis, synovial and joint capsule thickening, and associated inflammation.

These changes lead to joint failure and associated symptoms: pain, tenderness, stiffness, loss of function and limitation in activity.

Changes in the individual tissues of the joint affect the functional cooperation between the joint tissues necessary for maintaining the function of the joint as an organ.

Although pathological changes in some way explain the pain mechanisms involved OA, structural alterations are also commonly found in individuals with no joint pain (Guermazi et al 2012)

This suggests that other factors contribute to the pain experience.

OA may be best conceptualised within a biopsychosocial framework, in which pain results from a complex interaction between structural changes, social and psychological factors (Dieppe & Lohmander, 2005, Hunter et al, 2008, Hunter et al, 2013).

This highlights the need to assess and address physical, psychological and social factors when managing a patient with OA, reinforcing the need for a multi-disciplinary approach.

Burden of OA is enormous, it is the most common chronic joint disorder.

It is a clinical syndrome of joint pain accompanied by varying degrees of functional limitation and reduced quality of life (NICE 2014).

More common in people aged 45+ but not simply a consequence of ageing.

In 2010, OA was identified as the eleventh leading cause of years lived with disability (YLD) at a global level (Vos et al 2012).

The prevalence of OA is likely to continue to rise as the population ages (Wilmoth 2000) and as levels of obesity, a risk factor, continue to grow (James 2008).

The cost implications of OA are considerable, with costs related to lost productivity, community and social services for OA, and from a range of treatments, particularly knee joint replacement surgery (OECD 2011).

The reported prevalence of OA varies greatly, depending on the definition of OA used (commonly defined as radiographic, symptomatic or self-reported OA).

There is general agreement that symptomatic or self-reported OA is more common than radiographic OA in any given joint among older people (NICE 2014).

This may be due to joint pain arising from causes other than osteoarthritis (for example, bursitis, tendonitis), differing radiographic protocols views of a joint, or the insensitivity of radiographs for detecting structural abnormalities that are better seen with imaging modalities such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (NICE 2014).

The occurrence of OA differs according to the geographical area and countries, since these are associated with variation of risks, genetic, environmental factors. For example, congenital acetabular hip dysplasia increases the risk of hip OA while squatting predisposes to knee OA, but protects from hip OA. Thus, interpretation of epidemiological studies on OA should take into account the geographical origin (Cimmino & Parodi 2005).

The knee is the most clinically significant site affected by OA.

The age- and sex-standardized incidence of knee OA is 240⁄100,000 person-years.

The incidence of hand OA is 100⁄100,000 person-years, for hip OA it is 88⁄100,000 person-years (Oliveira et al 1995).

In the US, the prevalence of clinical OA has grown to nearly 27 million, up from an estimate for 1995 of 21 million, as would be expected for such a strongly age-related disease (Lawrence et al 2008).

The prevalence of OA is higher in women than men, especially after age 50 and for hand and knee OA (Peat et al 2001).

- Age and sex

- Obesity

- Occupational factors

- Joint deformity and laxity

- Acute injury and repetitive joint loading

- Muscle weakness

- Genetics

- OA appears to be strongly genetically determined with genetic factors accounting for at least 60% of hip and hand OA and up to 40% of knee OA (Spector 2004). However, the specific genes involved in OA susceptibility have yet to be confirmed in all ethnicities and populations (Johnson & Hunter 2014).

Pain: It typically occurs after joint use and is relieved at rest. With disease progression, pain occurs in minimal motion or even at rest and finally even during sleep.

Stiffness: Stiffness may also occur in the morning or after periods of inactivity during the day. Morning stiffness generally resolves after less than 15 minutes.

Functional Limitation: Limitations of functions and activities develop as OA progresses. People report e.g. limitations in kneeling, for knee OA, or cutting one’s toenails for hip OA. OA can also hamper stair climbing, walking and performing household chores. In weight bearing joints an abrupt ‘giving way’ may occur. In hand OA, impaired hand function is associated with the severity of OA, pain, joint involvement and the presence of nodes (Bagis et al 2003).

Psychological Impact: Furthermore, symptomatic OA may be associated with depression and disturbed sleep, which are additional contributors to disability (Allen et al 2008).

Quality of Life: Thus, OA, wherever it occurs, typically causes pain, alters function and leads to a significant deterioration in the quality of life (CDC 2001).

Pain severity is associated with increase in mobility problems

According to WHO, about 80% those with OA have limitation in movement and quarter have limitations in ADL

Joint pain can affect mobility, participation and the psychosocial functioning of the individual, leading to increased dependency in carrying out ADL

Reduced quality of life and depression are also linked to OA

Joint Swelling: Joint enlargement results from joint effusion and/or osteophytes and/or synovitis. Bony swelling is easily recognized in superficial joints such as the finger joints or knees. A synovial effusion may be seen during OA flares, but can also occur during chronic phases as a persistent feature.

Joint Tenderness: Joints are usually tender during active motion testing and under pressure. Crepitus is commonly felt on passive or active mobilization of an OA joint.

Joint Deformities: Reflect advanced disease resulting from cartilage loss, collapse of subchondral bone, formation of bone cysts and bony overgrowth. This destruction contributes to misalignment, joint instability and limb (usually manifest as leg) shortening.

Gait: Examination of the legs with the patient standing and walking is necessary to investigate the presence of malalignment and abnormal gait.

Functional testing is used to assess muscle strength, mobility, balance, and coordination, but also stability, as this plays an important role in the patient’s functional performance.

Overall assessment, global pain or disability can also be quantitatively evaluated using simple tools such as a five-point Likert scale (none, mild, moderate, severe, very severe), or on a 100 mm Visual Analogue Scale (VAS).

Pain can also be assessed indirectly by estimating the symptomatic treatment required, such as the number of days per week that drugs are required or their consistent dose usage (Constant et al 1997).

One of the instruments widely used to assess pain and disability is the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities (WOMAC) composite index (Bellamy et al 1988). It is used mainly for the knee or the hip.

The Knee injury OA Outcome Score (KOOS) is a 42-item self-administered knee-specific questionnaire.

The Foot and Ankle Outcome Score (FAOS) and Hip disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (HOOS) are also available (Nilsdottir et al, 2003; Roos et al, 2001).

Impaired function in hand OA can be assessed in clinical trials using the Functional Index for Hand OA (FIHOA) or the Australian/Canadian OA Hand Index (AUSCAN) (Dreiser et al 2000, Allen et al 2006, Bellamy et al 2002).

Objectives

patient education and information access

pain relief

optimisation of function

beneficial modification of the OA process

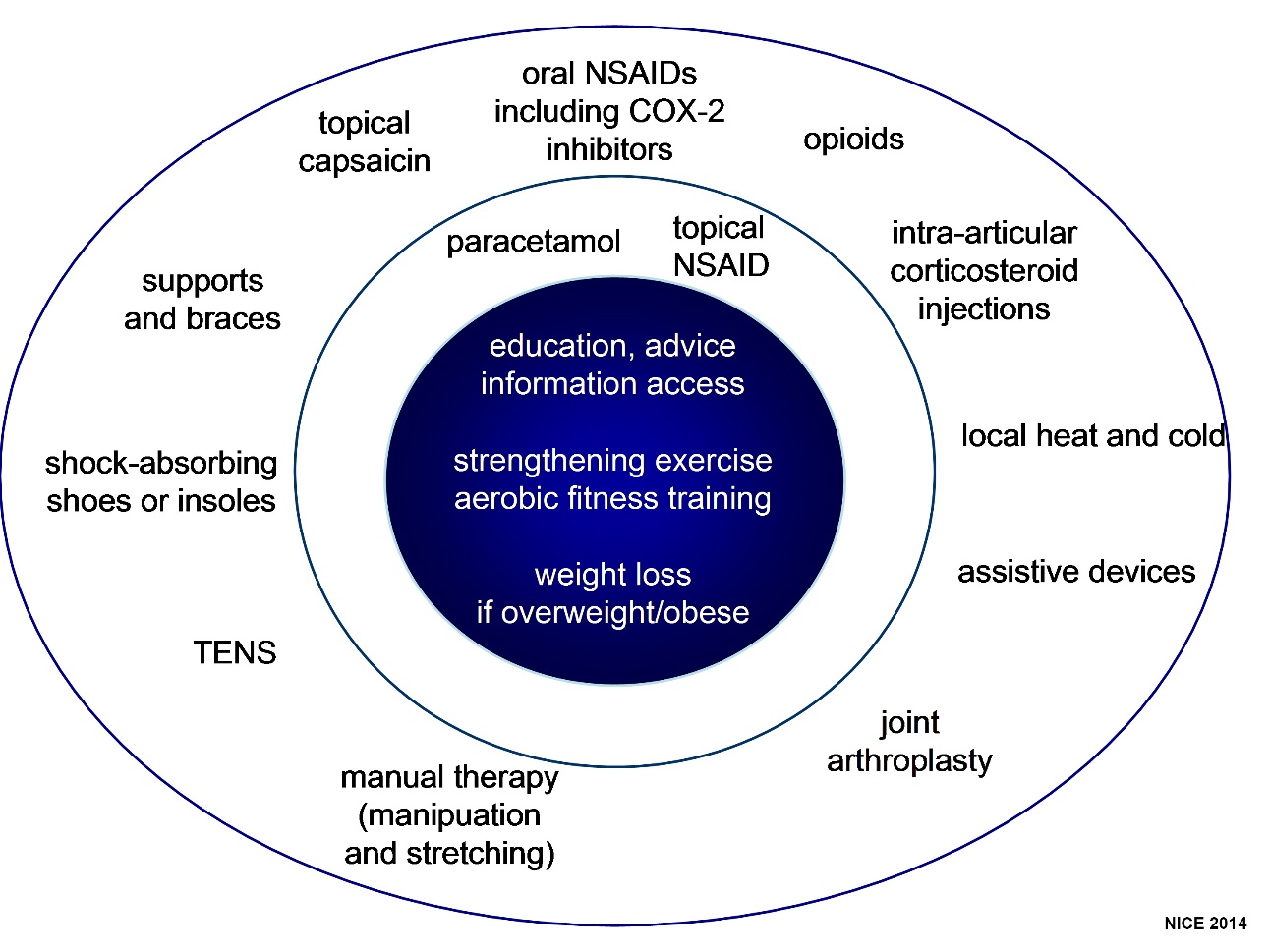

Management of patients with OA needs to be individualised and patient centred based on a thorough, holistic assessment and competent examination. Making, giving and explaining the diagnosis in positive terms is a valuable starting point (Porcheret et al 2014).

Numerous factors influence treatment selection, for example OA related factors such as the joint involved, whether more than one joint is affected, the degree of structural damage, and the level of pain intensity.

Person specific factors, such as age, required daily activities (occupation, leisure), patient expectations, number of joints affected and perceptions of OA all modify the approach that is taken. Comorbidity, such as cardiovascular diseases, and the respective concurrent medications are important and almost inevitable in the older population affected by OA.

There is a wide selection of treatment options for OA.

However, except for intra-articular (IA) corticosteroid or surgery, the effect size of the majority of OA treatments is only modest.Therefore, successful management requires the use of multiple components, both non-pharmacological and pharmacological, rather than a monotherapeutic approach.

Management should always contain the core elements of education and information access, exercise and weight loss if overweight or obese, together with any adjuncts that are thought appropriate. Such a ‘core plus option’ approach has been emphasised particularly by NICE (2014)

Footwear

The worst design shoe (left) for health of feet, knees and hips, having a thin hard sole, narrow raised heel, narrow forefoot and shallow uppers. The better shoe on the right has a thick soft sole, no raised heel, broad forefoot and deep soft upper.

A review of the effectiveness of the use of lateral wedges insoles in patients with medial knee OA found no significant benefit on pain or function (Fernandes et al 2013).

Historically, medial wedged insoles have been recommended for patients with lateral tibiofemoral OA or mild valgus malalignment.

However, there is no clear evidence to support the use of one type of insole over another, and adverse effects including foot sole pain, low back pain and popliteal pain have been reported.

As a result the recent EULAR non-pharmacological guidance document did not recommended the use of wedged insoles (Fernandes et al 2013).

Sticks and Walking Aids:

There is a wide range of walking sticks and walking aids to suit the individual. These can all reduce mechanical loading across a knee or hip that is compromised by osteoarthritis.

Patients should be given formal instruction in the optimal use of a cane or crutch in the contralateral hand (Jones et al 2012).

Frames or wheeled walkers are often preferable for those with bilateral disease and are particularly helpful for certain tasks requiring walking and carrying—for example, when out shopping.

There is a sound biomechanical rationale for the use of a walking stick and observational evidence that use of a stick in the contralateral hand reduces the adduction moment across the medial tibiofemoral compartment and mechanical loading through the hip.

Use of a stick or walking aid is recommended in all guidelines for knee and hip OA (Brosseau et al 2014, Larmer et al 2014, Nelson et al 2014). Some individuals have negative perspectives on using walking aids, so, as always, a detailed discussion with the patient and a clear explanation of benefits is required.

Braces, Splints etc:

There is a wide range of braces, splints are other biomechanical approaches available for people with OA.

In patients with knee OA and mild to moderate varus or valgus instability or malalignment, a knee brace can reduce pain, improve stability, and diminish the risk of falling. A variety of mechanical bracing devices are available now ‘off the shelf’ and manufacture of an individualised brace is usually not required. The principle is not to overcompensate and shift load bearing between medial

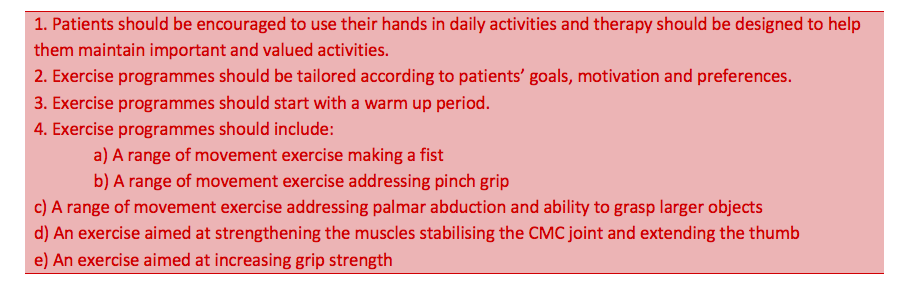

For patients with severe symptomatic thumb base OA, splints are recommended for pain relief and to correct lateral angulation and flexion deformity. As part of core management, patients should be advised on pacing of hand usage, and to avoid repetitive power grip, pinch, and twisting movements.

Use of Assistive Devices for Joint Protection:

For patients with pronounced symptoms and functional difficulties from hand, hip or knee OA, adjunctive assistive devices may be required to modify the patient’s environment in a way that reduces mechanical loading and facilitates specific actions.

As part of core management, patients should be advised on pacing of hand usage, and to avoid repetitive power grip, pinch, and twisting movements (joint protection).

Examples for hand OA include enlarged grips on pens or cutlery for writing and eating, small non-slip mats to assist opening objects, and electric can openers in the kitchen (Zhang et al 2007a, Fernandes et al 2013).

International guidelines recommend the use of joint protection as an effective intervention for medium term outcome. Joint protection education should be delivered using cognitive behavioural approaches to be effective!

For knee or hip OA, replacing a bath with a walk-in shower or using raised toilet seats and chairs may be beneficial (Fernandes et al 2013).

Thermotherapy:

- Thermotherapy is locally applied heat or cold. There is little research evidence but it is used widely by patients with OA. Heat can be applied in various ways such as application of heat packs, by immersion in warm water or wax baths or by diathermy, while local cold is usually administered by ice packs or by massage with ice. Heat and cold is recommended in most guidelines as a simple and safe adjunct to the self-management of pain (Fernandes 2013, NICE 2014).

Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation:

- Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) may give safe and effective pain relief in some patients with OA and is recommended as a safe adjunctive modality in the majority of guidelines. Due to the poor quality and reporting of included studies, latest review could not firmly conclude whether TENS is effective for pain relief, although there was no evidence of it being unsafe (Rutjes et al 2009).

Acupuncture:

Acupuncture is an ancient treatment with multiple potential mechanisms of action including release of endogenous opioid. It is practised by many allied health professionals, but although there is an extensive research base examining the efficacy of acupuncture, interpretation is difficult because of variability both in delivery and in controls.

A recent Cochrane review by Manheimer et al (2010) included sixteen RCTs (3498 people) comparing acupuncture to either a sham, waiting list control or another active treatment in people with knee, hip, or hand OA.

Authors concluded that although sham-controlled trials show small statistically significant benefits these are not of clinical relevance and are likely, in part, due to incomplete blinding. The statistically significant and clinically relevant benefits of acupuncture to waiting list-controlled arthritis suggest are likely due to expectation or placebo effects (Manheimer et al 2010)

Inflammatory Diseases

At times of infection, trauma, or other causes of harm to the body, inflammation plays a very important role in protecting the injured tissue from further infection and starting the healing process. It does this by increasing blood flow to the damaged tissue to both deliver important blood cells and proteins and wash away unwanted breakdown products or debris.

In an inflammatory disease, inflammation occurs by mistake.

Increased blood flow and cells arrive at a given site, causing heat, swelling, pain and loss of function, but there is no infection and no trauma has occurred. Attacking the body without an external insult in this way is called autoimmunity.

Inflammation can also cause:

Enlargement and loss of function of the kidney (as in SLE)

Swelling and loss of function of blood vessels (as in Vasculitis)

Swelling and loss of function of muscles (as in Juvenile Dermatomyositis)

Any organ can be affected in this way

The Latin root word is rheumaticus, “troubled with rheum,” and rheum itself is a Greek word that means “flow.” The word was first ascribed to the disease of rheumatism because of the way it seemed to spread — or flow — within a patient’s body.

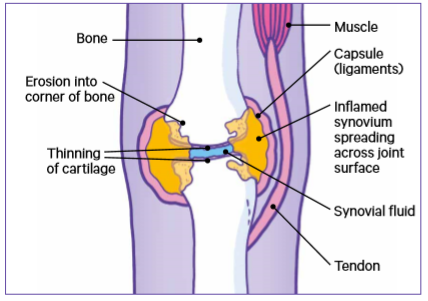

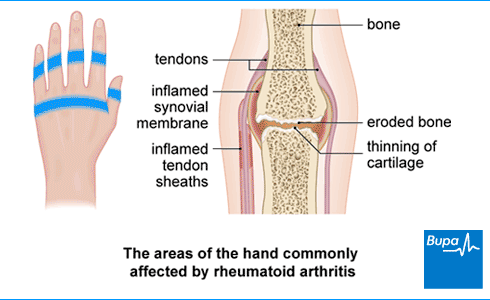

Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) is a chronic inflammatory disease that typically affects small and medium-sized joints in a symmetric fashion.

It is characterised by persistent synovitis, articular damage and systemic inflammation that may cause extra-articular manifestations and comorbidities, such as pulmonary and cardiovascular diseases.

Because of these comorbidities, uncontrolled RA is associated with a reduction in life-expectancy (Avina-Zubieta et al, 2008).

Loss of axial bone mass

Potentially self perpetuating

Endothelial damage

- A common and early event in cardiovascular disease (CVD) happens when damage occurs to the vascular endothelium, the thin layer of cells that lines blood vessels. This damage impairs the function of the endothelium, a condition called endothelial dysfunction.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) affects approximately 0.5-1.1% of European and North-American adults.

There are considerable regional variations in incidence and prevalence with lower estimates for Southern European, Asian and African countries (Alamnos et al, 2006).

The disease can onset in all ages, but median age for disease onset is 55 – 60 years and a shift towards onset at an older age has been described (Uhlig & Kvien, 2005).

RA is more common in women than in men and the female: male ratio is approximately 3:1 (Crowson et al, 2011). However, after menopauses, the incidence for women approaches the incidence for men.

RA seems to cluster in families; the likelihood that a first-degree relative of a patient will share the diagnosis is 2–10 times the population prevalence of the disease, and recurrence risks are highest for relatives of the most severely affected patients (Hemminki et al, 2009).

Why an individual person develops RA is partly known and partly unknown.

Several factors, such as genetics, environmental and accidental factors have to act in an orchestrated manner at different time points. Results from twin studies indicate that 50-60% of the risk is attributed to genetic risk factors.

RA is considered to be autoimmune in nature, i.e. in genetic disposed individuals, the immune system may react with production of antibodies that predisposes for development of the disease. Higher levels of ACPA are associated with a more severe disease course (Meyer et al, 2006).

- ACPA: ACPA is an antibody against citrullinated peptides, which is found in 60-70% of RA-patients, but hardly ever in other diseases or in healthy subjects (Van Gaalen et al, 2005).

Rheumatoid Factor (RF) is an antibody against IgM, IgG- and IgA- that are present in about 60-70% of RA patients (Nishimura et al, 2007).

However, RFs role in development of RA remains unclear because it is also found in infectious diseases, autoimmune diseases other than RA and in up to 15% of healthy, mostly elderly individuals.

Despite this lack of specificity, the presence of RF was included in the diagnostic criteria for RA defined by the American College of Rheumatology in 1987 (Arnett et al, 1988) and is still included in the ACR/EULAR 2010 classification criteria for RA.

Cigarette smoking is the most important environmental risk factor for RA. Smoking has been shown to be a risk factor in ACPA positive RA, with no or minor contribution in ACPA negative patients (Klareskog et al, 2009).

RA is a heterogeneous condition with a variable disease course.

Some patients have an acute disease onset with fever, polyarthritis and extra-articular manifestations, but it is more common with a gradual and insidious onset.

Cardinal symptoms of RA are pain, stiffness and swelling of the involved joints; redness and warmth are less common.

Concomitant nodules, tenosynovitis, bursitis and even carpal tunnel syndrome may be present.

RA is a systemic disease as may be manifested by generalized weakness, weight loss and low-grade fever.

Fatigue, physical impairment and reduced health-related quality of life are frequently reported.

The systemic component may cause several extra-articular manifestations, including sicca syndrome, vasculitis, scleritis, pericarditis, pleuritis and interstitial lung disease, which are associated with increased mortality (Young & Koduri, 2007).

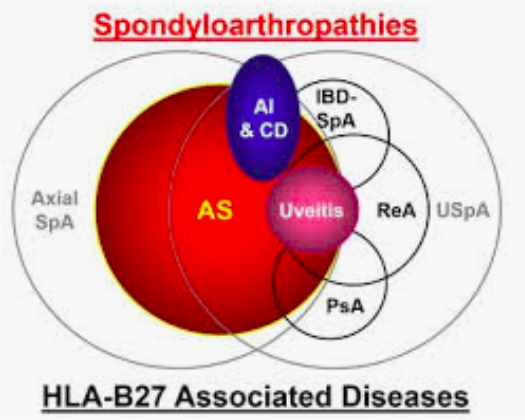

Seronegative Spondyloarthropathies

Inflammatory disorders originating at entheses

Ankylosing Spondylitis/ Axial SpA (AS)

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA)

Reactive arthritis

Overall prevalence around 1 in 300

No rheumatoid factor

Spinal involvement

Asymmetrical arthritis

Lower limb more often

Enthesopathy

Association with skin and eye problems

Genetic link with HLA B27

Stiffness and pain in the lower back in the early morning which eases through the day or with exercise

Pain in the sacroiliac joints and the spine (the joints where the base of your spine meets your pelvis), in the buttocks or the backs of your thighs

Other symptoms may include;

- Tenderness at the heel

- Tenderness at the base of your pelvis

- Chest pain or a ‘strapped-in’ feeling

- Inflammation of the eye

- Inflammation of the bowel

PsA is characterised by stiffness, pain, swelling, and tenderness of the joints and surrounding ligaments and tendons.

Common findings include enthesitis (inflammation of the tendon insertion points on bone) and dactylitis (inflammation of the fingers).

It usually affects people who already have the skin condition psoriasis. This causes patches of red, raised skin, with white and silvery flakes.

It’s estimated that around one in five people with psoriasis will develop psoriatic arthritis.

Can be similar to RA

But more typically:

- Asymmetrical, few joints only

- Distal finger joint involvement

- Dactylitis

- Spinal inflammation

-No relation between joint and skin severity

Mixed Connective Tissue Diseases (MCTD)

Mixed connective tissue disease is a term used to describe a disorder characterised by features of systemic lupus erythematosus [SLE], systemic sclerosis [SS], and polymyositis.

Raynaud phenomenon, joint pains, various skin abnormalities, muscle weakness, and problems with internal organs can develop.

The diagnosis is based on symptoms and the results of blood tests to detect levels of characteristic antibodies.

Despite treatment, mixed connective tissue disease worsens in about 13% of the people, causing potentially fatal complications. Causes of death include pulmonary hypertension (mainly) and heart disease. The prognosis is worse for people who have mainly features of systemic sclerosis or polymyositis.

Mixed connective tissue disease does not appear to shorten life expectancy, except for people who have certain features, such as those of systemic sclerosis, polymyositis, pulmonary hypertension, or heart disease.

People who have mixed connective tissue disease are at increased risk of atherosclerosis, are closely monitored by doctors, and are treated for specific symptoms and complications of atherosclerosis as they occur.

Common symptoms include painful and swollen joints, fever, chest pain, hair loss, mouth ulcers, swollen lymph nodes, feeling tired, and a red rash which is most commonly on the face. Often there are periods of illness, called flares, and periods of remission during which there are few symptoms. Rate of SLE varies between countries from 20 to 70 per 100,000. Women of childbearing age are affected about nine times more often than men.

Characterised by diffuse fibrosis and vascular abnormalities in the skin, joints, and internal organs (especially the esophagus, lower GI tract, lungs, heart, and kidneys). Common symptoms include Raynaud phenomenon, polyarthralgia, dysphagia, heartburn, and swelling and eventually skin tightening and contractures of the fingers. Lung, heart, and kidney involvement accounts for most deaths. Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is about 4 times more common among women than men. It is most common among people aged 20 to 50 and is rare in children. Overall 10-yr survival is about 65%.#

Polymyositis is one of the inflammatory myopathies, a group of muscle diseases that involves inflammation of the muscles or associated tissues, such as the blood vessels that supply the muscles. A myopathy is a muscle disease, and inflammation is response to cell damage. The muscles of the shoulders, upper arms, hips, thighs and neck display the most weakness in PM. There also can be pain or tenderness in the affected areas, as well as swallowing problems and inflammation of the heart and lung muscle tissues. PM usually begins after age 20, its progression is gradual and not life threatening.

Articular disease

Extra-articular disease - Multisystem involvement

Organ damage

Associated disorders

Disability

Co morbidity

Anaemia:

Chronic Disease

Iron Deficiency

Marrow suppression

B12 Deficiency

Haemolytic anaemia

Useful Tests:

Serum iron

Ferritin

Folic Acid

Vitamin B-12

Rheumatoid Factor:

60–80% of RA patients

Antibody found in RA

Can be negative

Not useful for monitoring disease

Many false positives

Anti CCP:

70–90% of RA patients

Anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPA)

May have prognostic value

Can be negative

May be present without RF

Not useful for monitoring disease

Anaemia:

Chronic Disease

Iron Deficiency

Marrow suppression

B12 Deficiency

Haemolytic anaemia

Useful Tests:

Serum iron

Ferritin

Folic Acid

Vitamin B-12

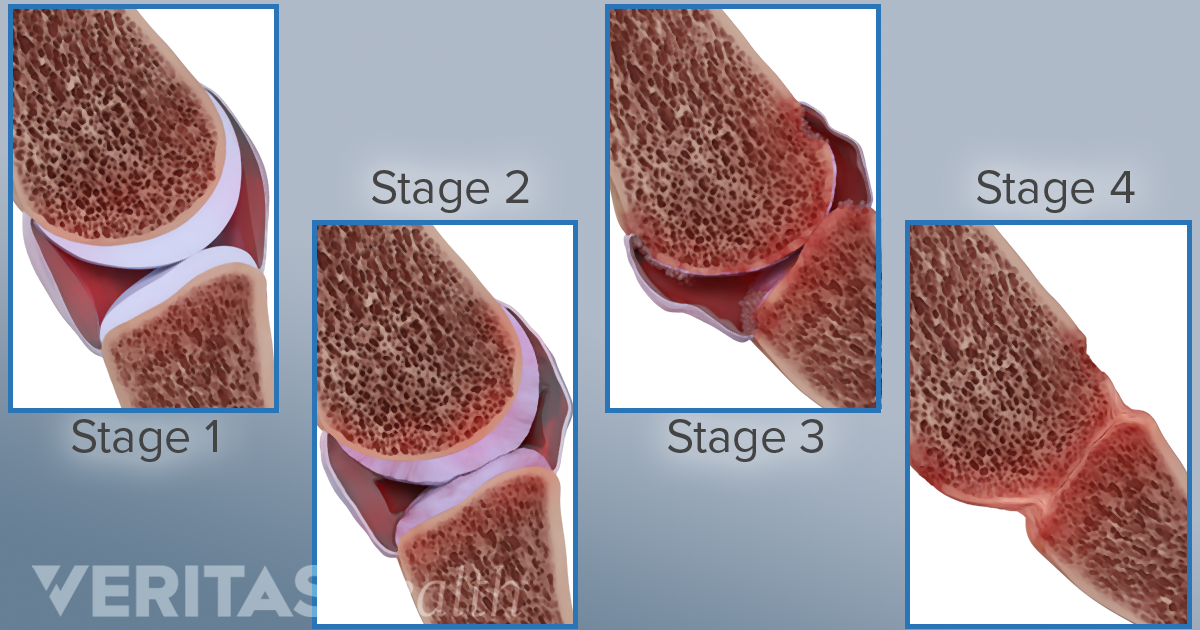

Joint Erosions:

Soft tissue swelling

Osteoporosis

Joint space narrowing

Marginal erosions

- Pannus eroding into bone

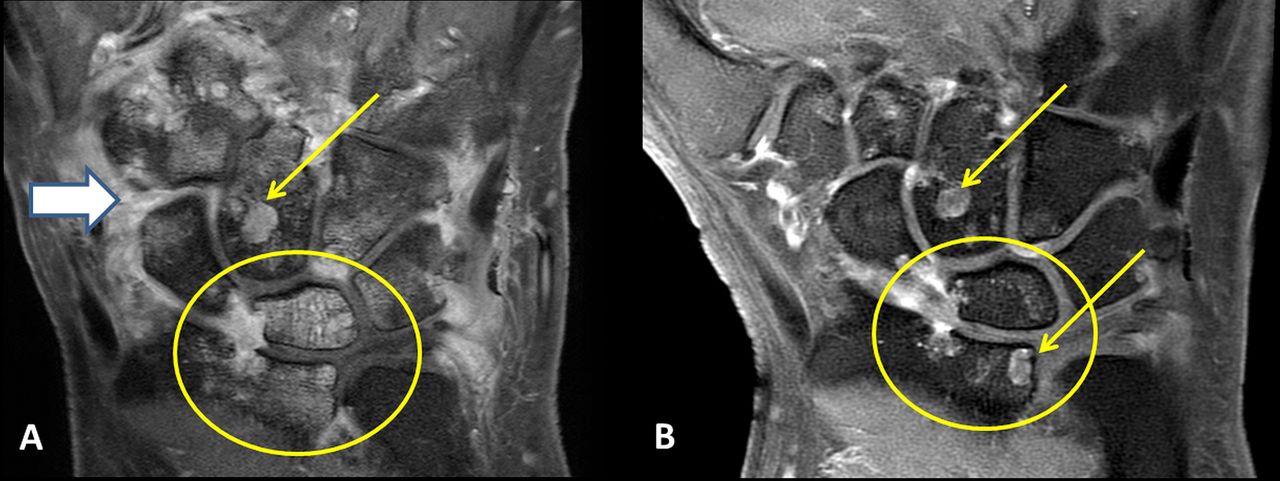

MRI:

MRI detects abnormalities in the soft tissues better than Xray at detecting early signs of RA

Can reveal:

- active inflammation occurring in the joint capsule

- early signs of bone inflammation that precedes permanent damage

Can detect bone oedema ( build-up of fluid in the bone marrow).

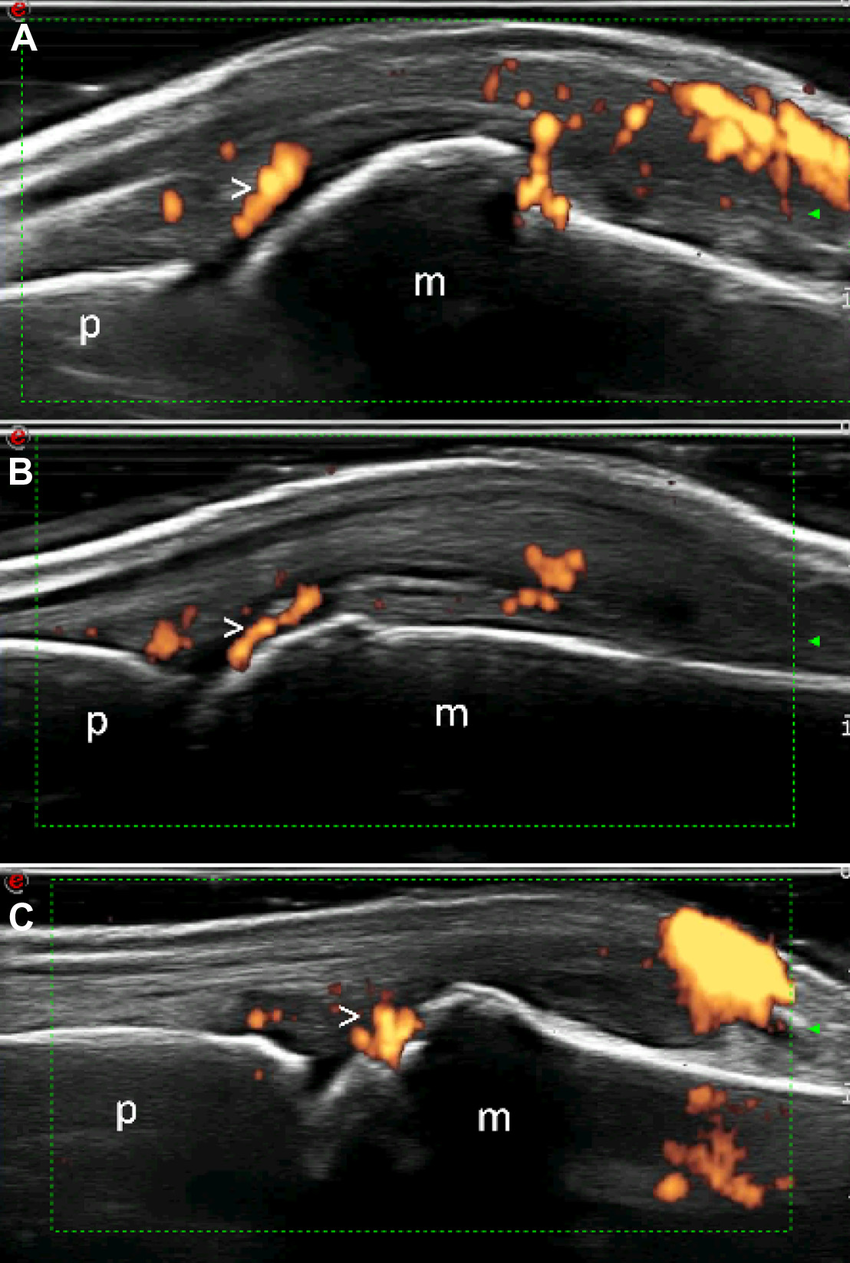

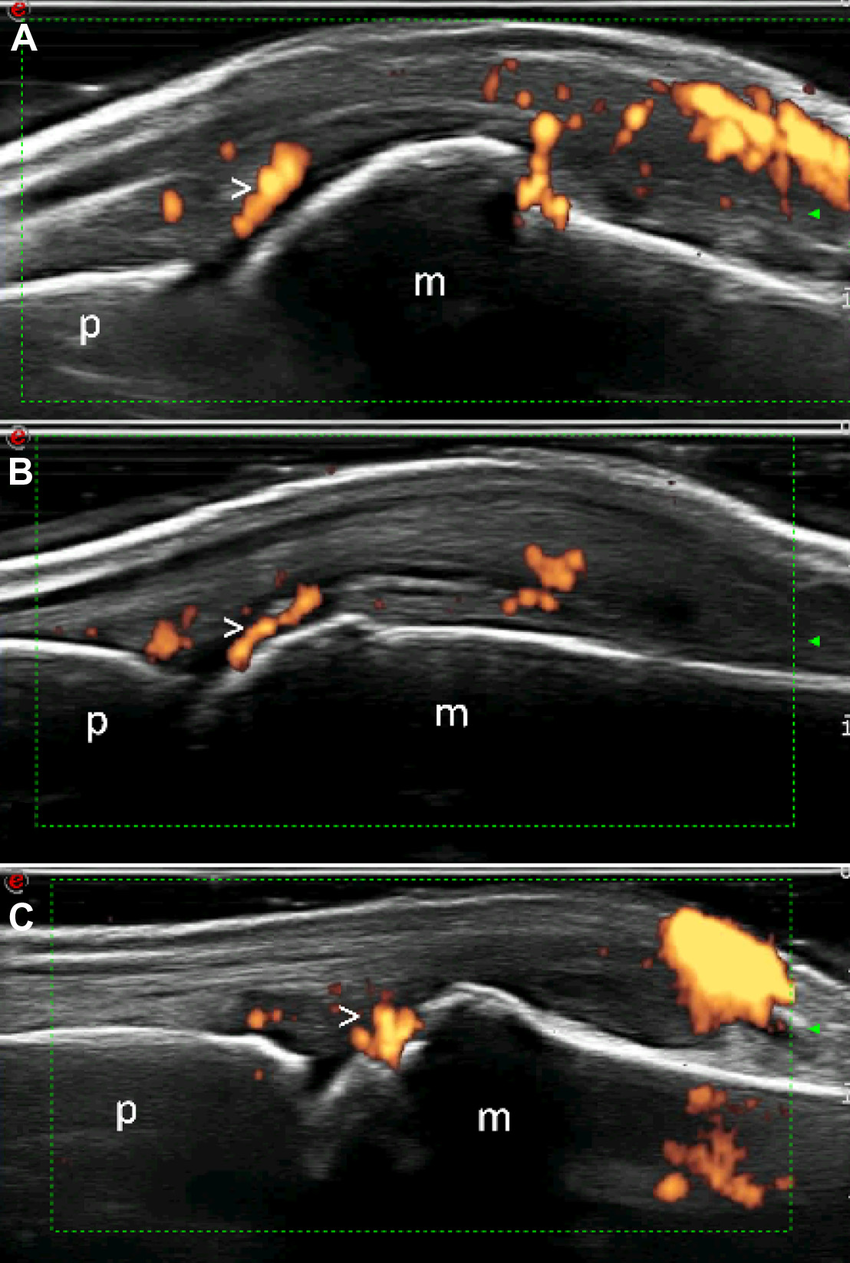

Ultrasound:

Uses high-frequency sound waves

Can detect erosions at early stage

Can reveal areas of joint inflammation by looking at blood flow.

Role in both diagnosis and monitoring disease Observer dependant

Disease Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drugs (DMARDs)

Symptom Control

- Control current inflammatory features

- Control current inflammatory features

Modify the course of disease

- Reduce joint damage and deformity

- Reduce radiographic progression

- Reduce long-term disability

Steps:

Use of early DMARDs

Step up / Step Down / Combination

Combinations of Conventional DMARDs : COBRA study

Combinations of Methotrexate plus Biologic agents

RA: Rehabilitation

| Rehabilitation Methods | Rehabilitation Methods |

|---|---|

| Activities of daily living (ADL) rehabilitation | Self-management education (group and individual) |

| Work rehabilitation: including on-site work assessment, ergonomics/ adaptations, employer liaison, work environment adaptation, functional capacity evaluation and work hardening | Joint protection training; energy conservation/ fatigue management and sleep hygiene training |

| Exploring voluntary work & adult education; leisure rehabilitation | Orthoses and Assistive devices |

| Stress and pain management | Hand and upper limb therapy & exercise |

| Relaxation training | Therapeutic activities |

| Communication and assertiveness training | Home assessment, recommending environmental modifications and housing adaptations |

| Counseling. (May also provide cognitive-behavioural therapy with post graduate training) | Mobility aids prescription (including wheelchair/powered aids) |

| Family/ carer liaison and support | Foot care advice |

| Advice on social security benefits and community resources | Exercise for health & well-being |

Cognitive-behavioural Approaches

Create a working relationship

- Recognise the person’s beliefs and priorities

- Ensure the person assumes responsibility

- Therapist approach MUST be positive

Create the motivation for change

- goal and value clarification: impact of RA on life; long goals/ changes want to make

- Discuss/reflect on pro’s and con’s of change: importance, confidence, readiness

- Investigate barriers to change

- Information giving

- Overcoming barriers

- Enable self-regulation:

- A: self-monitoring

- B: self-evaluation

- C: self-reinforcement

Follow a behavioural change programme:

Adequate practice with supervision

Enhancing self-efficacy through:

- Modelling

- Skills mastery (step-by-step)**

- Reinterpretation of physiological symptoms

- Verbal persuasion

Preparation & Action: Goal Setting

Identify long-term goals with client

Develop Action Plans of short-term goals (week by week):

- SMART: Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Realistic, Time-bound

Assess yourself honestly – be realistic

Action – be specific

- How much – eg 3 repetitions

- How Often – eg 3x/week

- How Sure – scale of 0-10

Plan for reward if achieve!