Upper limb Prosthetics

Introduction

David W. Dorrance, the original designer of the “Split Hook,” in 1912 (US Patent 1042413).

- Dorrance, lost his hand in 1909 in a sawmill accident, was unhappy with the immovable single “pirate’s hook,”

- He developed the split hook which allowed items to be squeezed and held in conjunction with a harness and straps

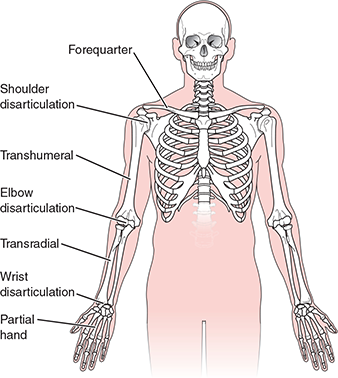

Level and Cause of Amputation

Number of referrals to UK disablement service centres in 2011⁄12 following a respective amputation at the appropriate level (bilateral in brackets):

- Forequarter: 12

- Shoulder disarticulation: 14

- Transhumeral: 95 (2)

- Elbow disarticulation: 3

- Transradial: 148 (3)

- Wrist disarticulation: 15

- Partial Hand: 70 (2)

- Loss of finger digit(s): 102 (2)

Twiste M. Limbless statistics, 2011⁄12 Available at: http://www.limbless-statistics.org/

Causes of Upper Limb Absence

- Trauma

- Congenital deficiency

- Cancer

- Infection

- Other

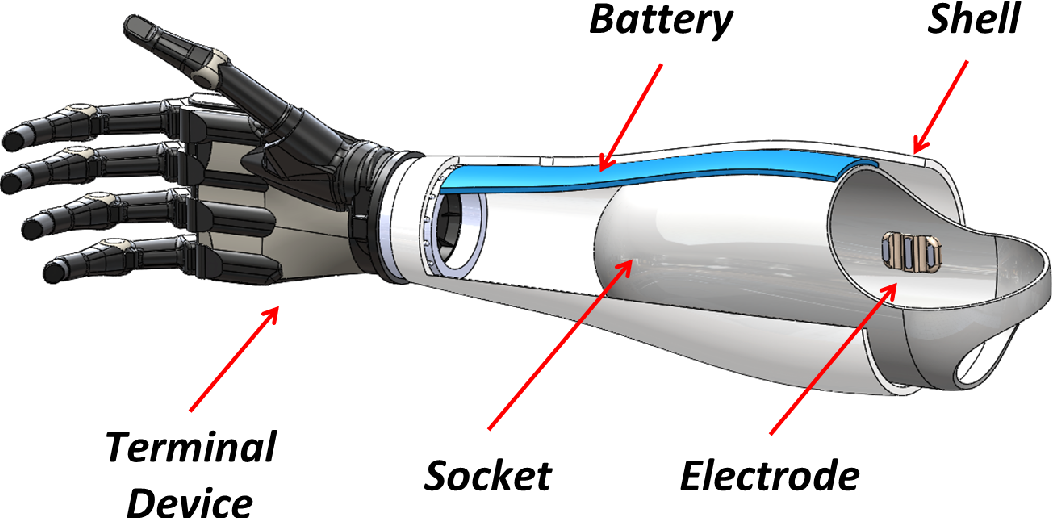

The Components of an Upper Limb Prosthesis

The socket, or prosthetic interface:

- Replacement joints, e.g. wrist, elbow

- Connecting elements

- Terminal devices, including hands

- Suspension systems, such as harnesses

- Control systems, such as myoelectric control

The Socket-Shape Capture, and Fit

Shape capture to create the correctly fitting socket usually begins with a plaster of Paris cast, that is rectified and used as a model to manufacture a prosthetic socket

Sockets are often contoured around existing bony anatomy, and can thereby suspend the prosthesis without any other form of external suspension system

Sometimes however this isn’t possible, or desired

Roll-on sockets

Developed by Ossur Kristinsson in the 1980’s, culminating in his paper

Prosthetics and Orthotics International, 1993, 17, 49-55. The ICEROSS concept: a discussion of a philosophy. Ö. Kristinsson.

ICElandic Roll On Silicone Socket (ICEROSS)

Employs ‘quasi hydrostatic’ suspension mechanism

Other Suspension Options

Fit 4 Purpose Prostheses

Upper Limb Functionality and Control: A Challenge to Reproduce

The natural upper limb is a complex tool, that is used to perform a wide variety of functions

From activities of daily living, to communication, social use and cultural applications, the natural hand and the arm has a wise range of functional and other applications which makes it very difficult to replicate

Types of Modern Prostheses

- Cosmetic prostheses

- Body powered prostheses

- Myoelectric prostheses

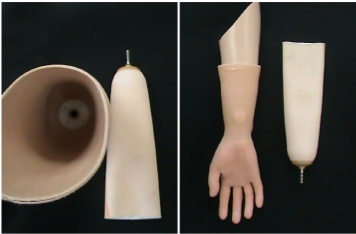

Cosmetic Prostheses

Designed to replicate the cosmetic size, shape and appearance of the missing limb, these can also act as basic holding or securing tools

They are the most commonly prescribed upper limb prostheses

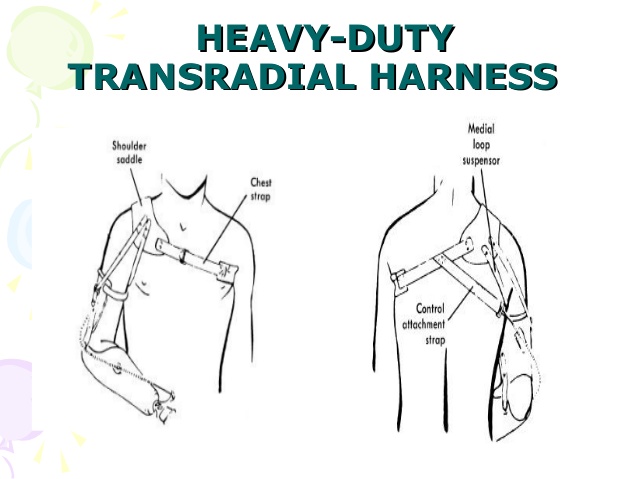

Body-powered Prostheses

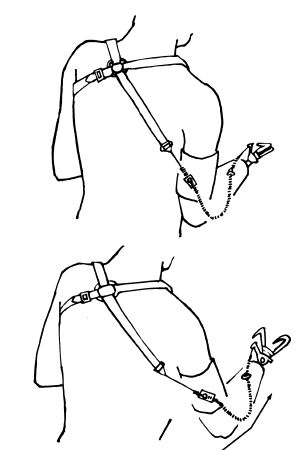

Uses a biomechanical harness: either a:

Full appendage - used to suspend and operate the terminal device in conjunction with a ‘cup’ socket, or a:

Simpler harness such as a P-loop (transradial only), which will only be used to operate the terminal device and will be used with a self suspending socket

Advantages: Good feedback, good control

Disadvantages: Poor cosmesis, dated design, comfort of harness

May be either active (with prehension) or passive (no prehension)

- Passive e.g. foam hands, knife appliance

- Active e.g. split hooks

- May be interchangeable when used in conjunction with single knob wrist rotary

Myoelectric Prostheses

Advantages over body powered devices:

- More powerful, greater grip strength and opening

- No need for harness for control

- Can potentially use limb in more positions around the body

- High-tec appeal

- Open to improvements in technology

Disadvantages:

- Heavy, costly, not as durable, harder to control, usually slower, less proprioception (feedback)

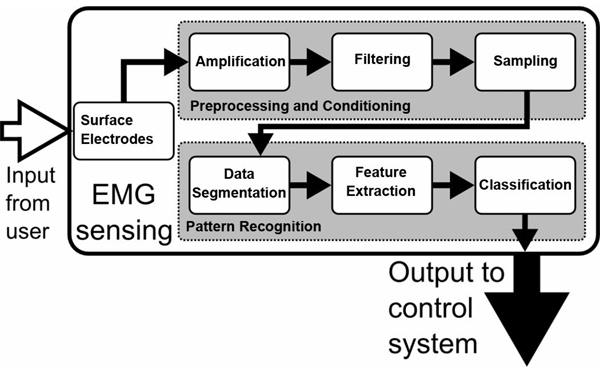

Myoelectric Signals

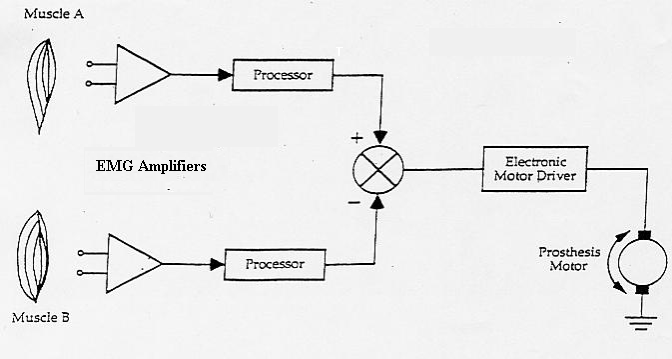

Created when muscles contract, these provide means of operating electrically powered prostheses

They are picked up and amplified via electrodes located within the inner wall of the socket

Myoelectric Control System

Types of Myoelectric Control

Threshold: 15 microvolts at skin’s surface; any signal above this = same response from hand

Proportional: 15 microvolts required for action again, but stronger signal=equivalent proportional response from the hand or component

Site/State: no. of electrodes used= no. of sites no. of functions = no. of states

Most hands are single degree of freedom hands, offering one grip type only

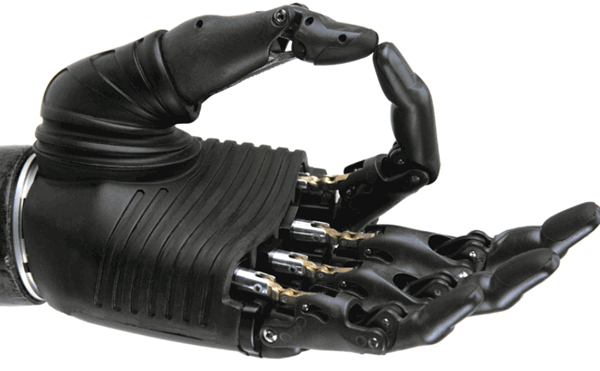

Multi-Functional Hands

- 14 grip patterns

- passive wrist options including low profile

- Full hand grip, individual motors in each finger and thumb

- 7 grip patterns

- Independently controlled thumb option

- Thumb, forefinger and middle finger grip

- Axon electric wrist option

The Clinical Reality

Real-world Usage:

Chadwell A, Kenney L, Granat MH, Thies S, Head J, Galpin A, Baker R, Kulkarni J. Upper limb activity in myoelectric prosthesis users is biased towards the intact limb and appears unrelated to goal-directed task performance. Scientific reports. 2018 Jul 23; 8(1):11084.

Actual Control

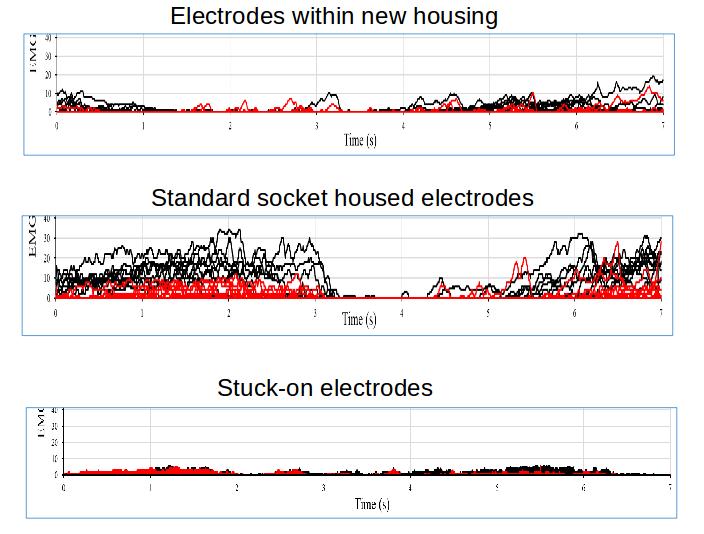

Head, J.S., Howard, D., Hutchins, S.W., Kenney, L., Heath, G.H. and Aksenov, A.Y., 2016. The use of an adjustable electrode housing unit to compare electrode alignment and contact variation with myoelectric prosthesis functionality: A pilot study. Prosthetics and orthotics international, 40(1), pp.123-128.

Current Challenges To Achieving Better Myoelectric Control

- Socket-related movement artefacts

- Size and clarity of signal

- Number of available control ‘modes’

Socket related movement artefacts: common mode voltage and its effects

The human body acts like a giant antenna, and attracts electricity from sources such as overhead power cables, the mains supply and electrical appliances

As a result, it constantly carries a ‘common mode voltage’ many times larger than a myoelectric signal

If the electrode is displaced in relation to the skin’s surface, then a movement artefact, very similar in size and strength to the myoelectric signal, will be produced

Filtering the signal

The common mode voltage is filtered using a differential amplifier.

As the contracting signal is discharged along the length of the muscle, the difference at each myode is registered as a positive and a negative signal and the difference is amplified

If the electrode moves or lifts, the common mode voltage may become active, or a small electrical signal may be caused by the electrode and the skin acting as charged capacitors

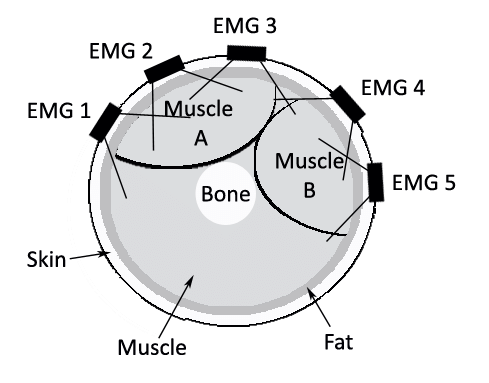

Size and Clarity of the Signal: Cross-Talk

Cross talk occurs when a muscle other than the target muscle affects the signal acquisition

Often occurs in congenital cases, where standard muscle boundaries are less well defined

Subcutaneous Fat & Surface Impedance

Subcutaneous fat will increase the chance of cross talk and dissipate the signal, reducing its strength at the surface

Surface impedance caused by skin particles, hairs and other barriers will also affect signal size and clarity

Kuiken, T.A., Lowery, M.M. and Stoykov, N.S., 2003. The effect of subcutaneous fat on myoelectric signal amplitude and cross-talk. Prosthetics and orthotics international, 27(1), pp.48-54.

Potential Solutions: Adjustable Electrode Housing, with De-coupling from the Socket

Use of an adjustable housing with de-coupling has produced an 83% reduction in signal production above prosthesis ‘activation’ thresholds during simple arm movements

Options to Improve Control Modes

Pattern Recognition

Englehart, K. and Hudgins, B., 2003. A robust, real-time control scheme for multifunction myoelectric control. IEEE transactions on biomedical engineering, 50(7), pp.848-854.

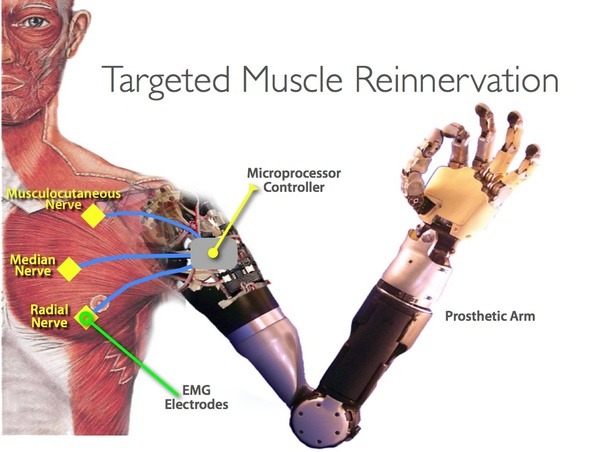

Targeted Muscle Re-ennervation

Kuiken, T.A., Li, G., Lock, B.A., Lipschutz, R.D., Miller, L.A., Stubblefield, K.A. and Englehart, K.B., 2009. Targeted muscle reinnervation for real-time myoelectric control of multifunction artificial arms. Jama, 301(6), pp.619-628.

Kuiken, T.A., Dumanian, G.A., Lipschutz, R.D., Miller, L.A. and Stubblefield, K.A., 2004. The use of targeted muscle reinnervation for improved myoelectric prosthesis control in a bilateral shoulder disarticulation amputee. Prosthetics and orthotics international, 28(3), pp.245-253.

Summary

Despite recent advances, we still have along way to go to improve upper limb prostheses, and particularly myoelectric control

Some options, such as simpler body-powered devices, would be of more benefit, particularly in developing countries and for sports and other activities

There are a number of factors that contribute to the prescription of the most suitable device, but these can be best reached with a sound understanding of each patients wishes, and requirements