Upper Limb Prosthesis Design

Introduction

Physical Properties of a Prosthetic Foot

- Un-deformed shape

- Mass

- Spring properties (conserves energy)

- Damping properties (dissipates energy)

The first challenge for designers is how to define the desired values for these properties, then to design a product to realise them

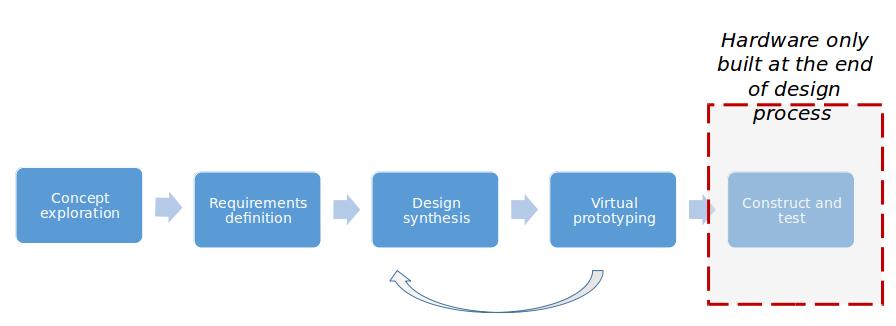

Engineering design process in the automotive/aerospace industry

- Concept Exploration

- Requirements Definition

- Design Synthesis

- Virtual Prototyping

- Construct and Test

Design Challenges

- Difficult to define requirements

- Construction and testing is very slow

- Limited detailed engineering standards for design characteristics

- Very limited real world data

- Multiple terrains to characterise

- Most studies compare specific prosthetic designs without a model to characterise their mechanical properties

- Designs may change faster than clinical trails can be completed

A Simple Design Framework

Model:

- Amputee independent prosthesis properties (AIPP).

- Mechanical properties of the prosthesis which directly influence comfort and performance

- e.g. AiPP model -> Major M, Twiste M, Kenney LPJ, Howard D. Amputee Independent Prosthesis Properties – A New Model for Description and Measurement. J Biomech 2011; 44(14): 2572-2575

Studies:

- Studies of amputee comfort and performance

- e.g. Hansen and Gard studies

- e.g. AIPP Performance studies

Remaining Challenges

The AIPP-based studies are not very common, and subject numbers generally low

Internationally agreed standards on how to characterise AIPP are needed

Better simulation models are needed to speed up early stages

Collaborations needed to collect larger data sets and speed up innovation

Characterisation of the foot and ankle now better understood, but what about other issues?

Upper limb mechanical prosthesis design examples

Upper limb Prostheses

Designed to replace the function and appearance of part of the upper limb

Very challenging specification

- Many degrees of freedom (hand has 27 degrees of freedom alone)

- Sensory feedback core part of function

- Requirement for low cognitive demand (much of natural hand control comes from spinal level)

- Cosmetically acceptable (ideally mimicking upper limb appearance?)

- Comfortable

How to describe the physical properties of a mechanical upper limb prosthesis?

- Mass properties?

- Aperture of the end effector?

- Mechanical efficiency of the transmission?

- Mechanics of the harness?

- Cable length and path?

Upper limb myoelectric prosthesis design example

How well do current myoelectric prostheses perform?

- Very little data

- Studies include very small participant numbers

- Studies limited by lack of intact control groups

- Self report of real world usage suggests poor levels of use and high levels of ‘rejection’

- The (very) few clinical studies of myo hands have tended to focus on a comparison between devices without any characterisation of the devices themselves (‘Hand A vs Hand B’ studies)

Developing a simple model of a myoelectric prosthesis

3 parameter model:

- Uncertainty arising from poor electrode contact (uncertainty in feedforward control)

- Delay in response of hand to EMG signal onset

- Skill in controlling EMG signal

Assessing uncertainty

Two metrics of uncertainty:

- Difference in number of unwanted activations and unwanted non-activations during reaction time tests (socket vs no socket condition)

- Difference in spread of reaction time performance (socket vs no socket condition)

Clinical measures of performance

The mostly highly rated performance measures included:

- Activities Measure for Upper Limb Amputees,

- University of New Brunswick Test of Prosthetic Skill and Spontaneity,

- Box and Block Test,

- modified Jebsen-Taylor Hand Function test light and heavy cans tests.

Most highly rated self-report measures were@

- DASH,

- Patient Rated Wrist Evaluation,

- QuickDASH and Hand Assessment Tool (HAT),

- International Osteoporosis Foundation Quality of Life Questionnaire

- Patient Rated Wrist Evaluation Functional Recovery subscale.

How should we characterise ‘performance’?

Self-report – captures, for example, the range of activities performed using a prosthesis, but subject to bias and recall errors. Based on an assumption that more tasks = better…?

Observing a defined set of tasks – defined set needed to allow comparison between subjects

Timing of performance of tasks – reasonable assumption that faster = more skilled, but this only reflects one facet of skill?

Unilateral amputees will often choose to use their intact limb alone perform tasks. How can we capture this?…. more on this, later…

Our choice of performance measures

Task Duration

Faster performance has consistently been linked to higher functionality.

Light et al. (2002); Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

Movement Variability

Higher levels of prosthesis experience correlate with lower levels of variability

Major et al. (2014); Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation

Major et al. (2015); 39th Annual Conference of the American Society of Biomechanics

Hand Aperture Profile

Prosthesis users demonstrate a plateau between hand opening and closing not seen in control subjects suggesting limited control over hand speed.

Bouwsema et al. (2010); Clinical Biomechanics

Gaze Behaviour

Increased time spent looking at the hand suggests uncertainty as to the state of the hand

Bouwsema et al. (2010); Clinical Biomechanics Sobuh et al. (2014); Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation

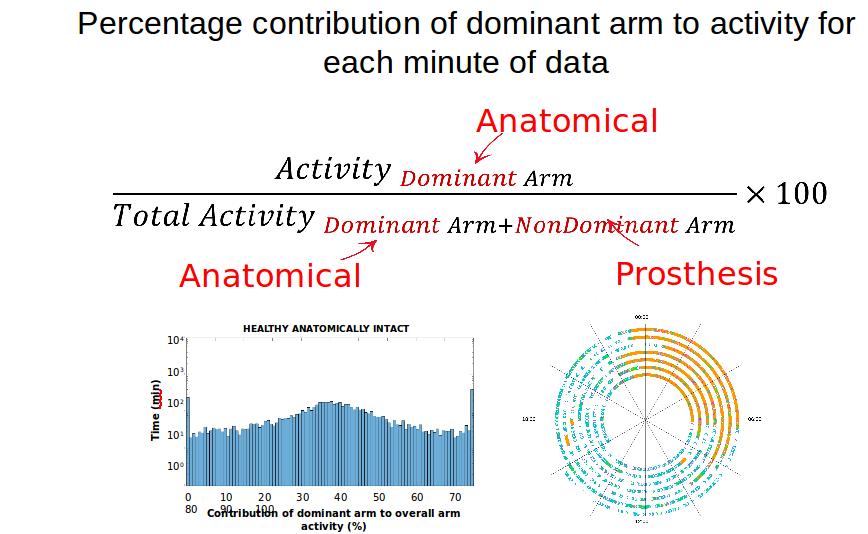

How to characterise use?

An arm with a prosthetic limb is impaired with respect to the intact limb

Implicit assumption may be that the better the prosthesis… or the performance of the user with their prosthesis?, the more it will be used in everyday life.

Promising metrics:

- Periods the prosthesis is worn

- Balance of activity between the prosthetic and intact arm

Affected limb/prosthesis:

- 3 axis acceleration data, typically sampled 30 times/second

- Signals processed to calculate activity counts (over 1 minute epochs)

- Magnitude (resultant) of 3 activity count values calculated

Unaffected limb:

- 3 axis acceleration data, typically sampled 30 times/second

- Signals processed to calculate activity counts (over 1 minute epochs)

- Magnitude (resultant) of 3 activity count values calculated

Future approaches

Big data

- New technologies coming through at a rapid pace

- Clinical evidence is not keeping pace

- How should we address this?

- Big data on real world use – perhaps the ‘acid test’ for any prosthesis?

- The more advanced upper limb prosthetic devices (e.g. i-limb) are already logging data on usage, but the data are not being (widely?) shared.

- One way forward might to develop industry standards on how/what data should be routinely collected (and made available)?

- The more advanced upper limb prosthetic devices (e.g. i-limb) are already logging data on usage, but the data are not being (widely?) shared.

Reality Check

Access to these technologies

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that more than one billion people are in need of one or more assistive products. The majority of these are older people and people with disabilities. With populations ageing and a rise in noncommunicable diseases, the number of people needing assistive products is projected to increase to beyond two billion by 2050.However, only one in ten people in need currently have access to assistive technology…..

Costs of new prosthetic tech

- Cost of devices averages around £46k

- Majority of amputees can’t access this technology

- The industry currently remains limited and specialised

Conclusion

- To design improved prostheses start by understanding the limitations with existing devices

- Models for characterisation of device properties are very useful, providing:

- A framework to define the desired properties, guiding design efforts

- We can use correlations between AIPP and performance measures to develop a design spec

- A framework with which to interpret clinical results across studies

- Longevity for clinical studies of devices

- Better standards both for representing properties of prostheses, and formalising the design process, are required

- Real-world studies help to highlight the real value of a given device to the users

References

Lower limb prosthetics and design

Major, M.J., et al., Amputee Independent Prosthesis Properties–a new model for description and measurement. J Biomech, 2011. 44(14): p. 2572-5

Major, M.J., et al., Stance phase mechanical characterization of transtibial prostheses distal to the socket: a review. J Rehabil Res Dev, 2012. 49(6): p. 815-29.

Major, M.J., et al., The effects of prosthetic ankle stiffness on ankle and knee kinematics, prosthetic limb loading, and net metabolic cost of trans-tibial amputee gait. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon), 2014. 29(1): p. 98-104.

Major, M.J., et al., The effects of prosthetic ankle stiffness on stability of gait in people with transtibial amputation. J Rehabil Res Dev, 2016. 53(6): p. 839-85

Major M.J. et al. Considering passive mechanical properties and patient user motor performance in lower limb prosthesis design optimization to enhance rehabilitation outcomes. Phys Ther Rev 22(3-4):p.1-15

Upper limb prosthetics and design

Bongers, R. et al., Bernstein’s levels of construction of movements applied to upper limb prosthetics. J Pros Orthot, 2012. 24: p.67-76

Chadwell, A., et al., The Reality of Myoelectric Prostheses: Understanding What Makes These Devices Difficult for Some Users to Control. Front Neurorobot, 2016. 10: p. 7.

Thies, S.B., et al., Skill assessment in upper limb myoelectric prosthesis users: Validation of a clinically feasible method for characterising upper limb temporal and amplitude variability during the performance of functional tasks. Med Eng Phys, 2017. 47: p. 137-143.

Chadwell, A., et al., Visualisation of upper limb activity using spirals: A new approach to the assessment of daily prosthesis usage. Prosthet Orthot Int, 2018. 42(1): p. 37-44.

Chadwell A, et al.. Upper limb activity in myoelectric prosthesis users is biased towards the intact limb and appears unrelated to goal-directed task performance. Scientific Reports (Nature), 2018. 8(1): p.11084

Chadwell A, et al.. Upper limb activity of twenty myoelectric prosthesis users and twenty healthy anatomically intact adults.. Scientific Data (Nature), 2019. 6(1):p.199